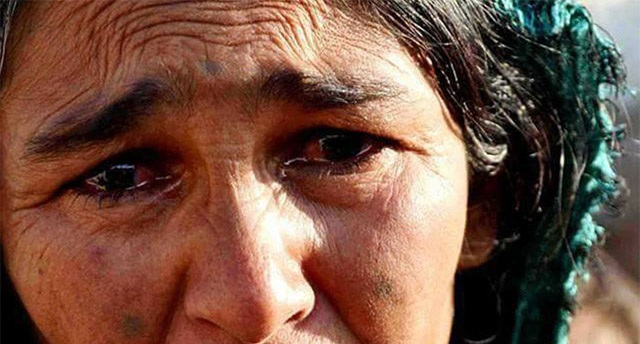

Violence against women – be it murder, beatings, mutilation, child marriage, the giving away of girls in marriage to resolve disputes (baad) or other harmful practices – remains widespread throughout Afghanistan, despite the government’s efforts to criminalise such practices, the UN has found. Its new report highlights how mediation by government and traditional actors, which is widely used to resolve cases of violence against women, deprives them of access to justice and hinders their fundamental rights. AAN’s Jelena Bjelica and Thomas Ruttig summarise the report’s key findings.

Injustice for women victims of violence – generally called survivors – and impunity for perpetrators are still widespread in Afghanistan. Most cases involving violence against women, including for the five ‘serious’ offences stated in Afghan Elimination of Violence against Women (EVAW) law – rape, enforced prostitution, publicising the identity of a victim, burning or using chemical substances and forced self-immolation or suicide (apart from murder, which is regulated by the penal code) – are not prosecuted by or adjudicated in courts. By contrast, more than a half of the 237 cases monitored by UNAMA between 2015 and 2017 were referred for mediation. The Afghan authorities, as evident from the UNAMA reports, exacerbate the situation for victims by allowing mediation mechanisms to resolve serious offences and by not carrying out their duty to investigate or prosecute these offences.

These are the key findings of a new UN report released today, 29 May 2018, in Kabul. The report, entitled “Injustice and Impunity: Mediation of Criminal Offences of Violence against Women” jointly prepared by the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) (read the full report here) is the sixth UNAMA report on violence against women since 2009, when the UN mission in Afghanistan began monitoring the implementation of the Elimination of Violence Against Women (EVAW) law.

The report is based on interviews and focus group discussions with survivors of violence and women’s rights activists as well as both traditional and government mediators. It is also informed by 237 cases of violence against women reported to EVAW institutions in 22 provinces monitored by UNAMA between 2015 and 2017 and 280 more cases of murder and “honour killings” documented throughout 2016 and 2017 by the UN mission. (1)

The legal framework: 2009 EVAW law and 2018 penal code

The EVAW law adopted in 2009 is a progressive law within the Afghan context. In addition to a broad approach to the issue of violence against women, including their harassment, the law also addresses forced and early marriage as well as polygamy for the first time in Afghan legal history (see this AAN analysis here).

However, the law has faced tough resistance from conservative circles, including in parliament, from the beginning. As a result, it was adopted by presidential decree, bypassing parliament. In 2013, MP Fawzia Kufi, the Wolesi Jirga’s (lower house) chairwoman of the Women’s Rights Commission, advocated pushing the presidential decree through parliament to make the EVAW law permanent. But she did so against the advice of other women’s rights activists, thereby risking a no-vote by the conservative majority. This was stopped by procedural tricks and as a result, the issue has still not been voted on by the lower house (see AAN dispatches here and here).

The new penal code adopted in 2018 also required a later amendment by presidential decree to make EVAW law crimes enforceable. Its draft had originally included a specific chapter on the elimination of violence against women, which, according to the UNAMA report, incorporated provisions to criminalise the majority of the 22 acts set out in Article 5 of the EVAW law. It had also included new provisions prohibiting both the detention of women on charges of “running away” and the practice of “exchange marriage,” or baad(when feuding families or clans exchange brides in the settlement of disputes). However, the final adopted version of the 2018 penal code did not include any reference to criminal offences of violence against women (with the exception of rape). The amendment was issued in a presidential decree (number 262) on 3 March 2018, which criminalised all five serious offences mentioned in the EVAW law.

While there is some political will among mainly women parliamentarians to vote on the laws, most MPs are still hostile towards criminalising violence against women, which, in Afghanistan, is often embodied in harmful traditional practices (honour killings and baad). As a result, EVAW-related issues have so far only been addressed through presidential decrees. This makes the existing legislation vulnerable to a backlash by the conservative majority in parliament.

Murders and “honour killings”

The UNAMA report found that the murder of women represents the second most prevalent form of violence against women in Afghanistan (the first being battery and laceration). UNAMA documented 280 cases of murder, including “honour killings” of women from January 2016 to December 2017. “Of these, 50 cases ended in a conviction of the perpetrator and subsequent prison sentences, representing 18 per cent of documented cases,” the report found, adding that “the vast majority of murder and ‘honour killing’ cases involving women never reached prosecution and the perpetrators are still at large.” (2)

UNAMA also found that in more than one third of cases documented over the two-year period, the police did not forward the cases to prosecutors. All of this, according to UNAMA, implies that the vast majority of murder and “honour killings” of women result in impunity for the perpetrator.

The report notes “deficiencies in Afghanistan’s applicable legislative framework for prosecuting ‘honour killings’ may have contributed to impunity during the period covered in this report.” This apparently has to do with the fact that “honour killings” are not criminalised in the 2009 EVAW law and appeared in Afghanistan’s 1976 penal code even as a mitigating factor to murder. Article 398 of the 1976 penal code states that “a person who kills or injures his wife or a relative in order to defend his honour will not be subject to the punishment for murder or laceration, and instead shall be imprisoned for a period of no more than two years.” The 2018 penal code, however, does not contain this reference and the justification of “honour killing” can no longer serve as a mitigating factor in murder trials, the UNAMA report said.

“Justice sector officials should investigate, prosecute and adjudicate ‘honour killings’ under the general murder provision in Article 512 [of the 2018 Penal Code], and sentence convicted persons accordingly,” the UNAMA recommended in its report.

Wide use of mediation: Misinterpretation of law and even “unlawful”

Of the 237 cases monitored by UNAMA, both traditional and government mediators resolved 145 cases. Mediators in most provinces informed UNAMA that these cases included murder, beatings, attempted rape, acid attacks and causing other injuries, domestic violence, “running away”, forced marriage, baad or forced suicide.

UNAMA found that EVAW institutions and non-governmental organisations not only conducted mediation proceedings, but also “referred cases to traditional mediation mechanisms, observed mediation sessions, or knew about mediation taking place, in relation to ‘honour killings’ and other serious offences stated in the EVAW Law.” The report said “Mediators in some provinces were either not aware of the limits on their authority to mediate cases, or did not admit to mediating the five serious offences, despite UNAMA findings to the contrary.”

According to UNAMA, the two different types of mediation carried out by traditional dispute resolution mechanisms related to violence against women – the mediation of criminal offences of violence against women and the mediation of wider disputes leading to decisions that result in violence against women – are both unlawful and constitute human rights abuses. An example given in the report states:

[…] Jirgas sometimes decide to give a girl in baad as a gesture of good will in order to resolve a dispute or criminal act between families. Traditional mediators however also mediated criminal offences of violence against women such as beating by spouses, harassment, causing isolation and more, in a similar way to the mediation carried out by EVAW institutions. In such cases, traditional mediators’ decisions largely involve commitment letters by the perpetrator to refrain from violence in the future.

The traditional mediation mechanism’s decision that is frequently harmful to women is often related to an exchange marriage. For example, UNAMA documented a case from the eastern region in which local families referred the case of a girl who had “run away” from her home because of an arranged marriage, to a jirga for resolution. The jirga decided, the report said, to give another 13-year-old girl from one of the families to the other family involved, in order to resolve the dispute. “The two families involved in this case insisted to the authorities that they had carried out a routine exchange marriage, which under the EVAW law may also be illegal,” the report said, adding that “UNAMA’s monitoring revealed that the illegal practice of baadhad taken place following the Jirga’s decision.” (3)

In nine provinces – Badghis, Paktya, Ghazni, Kunar, Maidan Wardak, Paktika, Khost, Balkh and Jawzjan – UNAMA found that mediators had adjudicated murder cases and that such practices were carried out almost exclusively by traditional dispute resolution mechanisms. Traditional mechanisms, the report states, “are not state-actors, and are not legally mandated to resolve criminal cases.” “Such mechanisms operate in an unofficial and unregulated capacity, their decisions in criminal cases are unlawful, and as such, are not subjected to any government oversight or scrutiny,” the report said.

This, according to the UNAMA report, amounted to misinterpretation of the EVAW law:

Article 39 of the EVAW Law is commonly used to justify referrals to mediation in criminal offences of violence against women. The article allows survivors to withdraw their complaint at any point of the judicial proceedings with the exception of the five serious offences, where the State is duty-bound to conduct investigations and prosecute such cases even without a complaint. The article however makes no reference to, or permits mediation.“

In spite of the large number of cases resolved through mediation,” the report said, “there are no policies on minimum standards of mediation, resulting in a great disparity of standards, procedures, referral of cases by EVAW institutions and capacity of the mediators.” Furthermore, the report said, there is no code of conduct or certification for mediators.

Furthermore, UNAMA documented that some survivors decided to withdraw their official complaints and agreed to mediation for fear of economic and social repercussions on their lives. For many survivors, the withdrawal of a complaint may be the only viable option, as dwindling international support has impacted the already limited shelter provisions in Afghanistan (see this AAN analysis on aid effectiveness); there are few other options for women who do not have the protection of their families. A recent attempt by the government to take financial control of around 40 non-government-run shelters, legal aid offices and halfway houses for women fleeing violence may further reduce the number of these safe havens for women (see here and here).

UNAMA further found that the main objective of mediators in violence against women cases was to achieve a re-unification of families, at the expense of criminal accountability and formal justice. “The woman’s choice about the matter is not properly taken into account,” the report said, adding that “insufficient or no attention is given to the protection of the survivor from future violence.”

The UNAMA report warns that there is no specific provision in Afghan law that permits or prescribes the mediation of criminal cases. It also highlights that the wide use of mediation in criminal offences of violence against women “promotes impunity, encourages the reoccurrence of violence and erodes trust in the legal system.”

“Where the five serious offences including murder and ‘honour killings’ were mediated by authorities or by others with the acquiescence of the authorities, this amounted to a direct breach of the EVAW Law, the Penal Code, and constituted a human rights violation on the part of the State,” the report said.

A vicious circle of violence

Many of the findings set out in the report are consistent with those previously published by UNAMA in 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013 and 2015. This indicates that despite some progress, the general situation has largely remained unchanged. The conclusions of the joint UNAMA-OHCHR report highlight how dire the situation is. They include that state officials frequently fail in investigating, prosecuting and punishing perpetrators and providing reparations to victims. This has contributed to the existing high rate of impunity and strengthens the normalisation of violence against women in Afghan society. The wide use of mediation promotes impunity, encourages the reoccurrence of violence, erodes trust in the legal system and is unlawful. Women’s access to justice remains limited, and women continue to face inequality before the law.

Traditional mediation mechanisms – which, in an increasing number of countries are prohibited legal tools in cases of violence against women – do not have a mandate and are insufficient to prosecute serious offences of violence against women. Mainly composed of men in a male-dominated society such as Afghanistan, their rulings are often extremely unjust and largely punitive towards women. The “honour killings” of women show a particularly brutal aspect of a society that is suffering from violent conflict and which annually claims the lives of over 10,000 civilians. Yet the fact that these cases go unprosecuted shows just how far the country has to go.

There is little hope that Afghanistan, which ranks 154 out of 157 on the global Gender Inequality Index (4), will reduce violence against women in a society that is largely misogynistic. As the UNAMA report shows, the perpetual cycle of violence against women extends beyond traditional communities, and unfortunately it is often the state that contributes to the further victimisation of survivors.

(1) Between 1 August 2015 and 31 December 2017, UNAMA selected 237 cases of violence against women reported to EVAW institutions in 22 provinces (Kunduz, Badakhshan, Takhar, Baghlan, Balkh, Samangan, Faryab, Jawzjan, Bamyan, Farah, Herat, Ghazni, Paktya, Khost, Kandahar, Kunar, Laghman, Nangrahar, Kabul, Panjshir, Parwan and Maidan Wardak) and monitored and documented their progress through the justice system. UNAMA conducted this monitoring in two separate tranches. Between 1 August 2015 and 31 March 2016, UNAMA monitored and documented 165 cases across 20 provinces; and between 19 January and 31 December 2017, UNAMA monitored an additional 72 cases across 21 provinces. The report’s key criteria for case selection were that cases of violence against women be criminalised by EVAW law and that cases could be monitored by UNAMA field teams through direct access to survivors.

UNAMA also documented and monitored 280 cases of murder and “honour killings”: 104 cases in 2016 and 176 cases in 2017.

In addition to monitoring the progression of cases, UNAMA conducted interviews and focus group discussions across Afghanistan, documenting the experience of survivors, mediators and women’s groups. UNAMA carried out 103 individual interviews with mediators and representatives of EVAW law institutions in 24 provinces (Badakhshan, Kunduz, Baghlan, Takhar, Faryab, Saripul, Jawzjan, Bamyan, Daikundi, Badghis, Farah, Ghor, Herat, Khost, Ghazni, Laghman, Kunar, Nangrahar, Paktya, Kandahar, Nimroz, Uruzgan, Zabul and Helmand); 44 focus group discussions with mediators in all 34 provinces; and 39 focus group discussions with women activists in all provinces. UNAMA consulted 1,826 mediators, representatives of EVAW law institutions and women’s rights activists.

(2) UNAMA’s findings in this regard are broadly consistent with those of the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission (AIHRC), which documented 160 murder cases of women during the first 8 months of 1395 (21 March to 21 November 2016) of which 119 were reported to be “honour killings”. According to the AIHRC only 33 percent of such cases were referred for prosecution. (AIHRC Report in Dari here).

(3) A new UNICEF study entitled “Child Marriage in Afghanistan: Changing the Narrative” and carried out in Bamyan, Kandahar, Paktya, Ghor and Badghis – in urban, semi-urban and rural locations informed by household surveys, case studies, focus groups and key informant interviews, found that 42 per cent of households in these provinces indicated that at least one member of their household had been married before the age of 18. However, the study shows significant disparities between provinces, from 21 percent of households in Ghor to 66 percent in Paktya reporting a marriage involving a child in their home.

(4) The Gender Inequality Index measures gender inequalities in three aspects of human development—reproductive health, measured by the maternal mortality ratio and adolescent birth rates; empowerment, measured by the proportion of parliamentary seats occupied by females and the proportion of adult females and males aged 25 years or older, with at least some secondary education; and economic status, expressed in labour market participation and measured by the labour force participation rate of men and women aged 15 years and older.

By Special Arrangement with AAN. Original link.

Disclaimer: Views expressed on this blog are not necessarily endorsed or supported by the Center for Research and Security Studies, Islamabad.