January 28, 2019

Meaningful negotiations are rooted in some major basic principles. First, an attitude prompting the negotiators to work for solutions that will benefit all or most of the participating parties. Second, an orientation that views the other person as a potential partner, rather than an adversary. Third, a climate that stimulates both parties to realize that they are more likely to attain their objectives if they work together rather than against each other. Fourth, a set of strategies that facilitate the process of securing mutual advantages. Hence, meaningful negotiations are never considered as a “zero-sum” game.

It seems that all these factors were at play – yet with some limitations – in the recent marathon talks between the US and the Taliban negotiators in Doha.

But the key is, before applying these principles, four aspects need to be well understood: a) separate people from the problem – in other words, be tough on issues not on people; b) focus on interests, not on positions; c) generate a variety of possibilities before making a decision; and d) define objective standards as the criteria for making the decision.

This does not come with a zero-sum game, but with continuous engagement. Whatever the case may be, the US and the Taliban talking to each other after 17 years of bloody conflict is in itself an achievement. Hopes for peace are highest than ever before.

According to the VOA news, the Afghan Taliban and the US officials on January 26, 2019, agreed on a preliminary draft of the likely peace accord. It was the first time the Taliban and the US officials held such a long meeting – extending to six exhaustive days.

Both the sides did not sign any formal arrangement but agreed on certain important points. There were several ups and downs but finally, as sources report, both players agreed on at least three vital agenda items. The US officials agreed to withdraw all their troops from Afghanistan in 18 months’ time. They would also have to lift a ban on Taliban leaders from the blacklist and will exchange prisoners. In return, the Taliban reportedly agreed they would not allow Afghanistan to be used by al-Qaeda and ISIS or any other militant organization against the US and its allies in future.

Afterwards, when three points are implemented, then both parties would work on other issues, including the formation of an interim government in Afghanistan, ceasefire and including the Afghan government in the peace and reconciliation process.

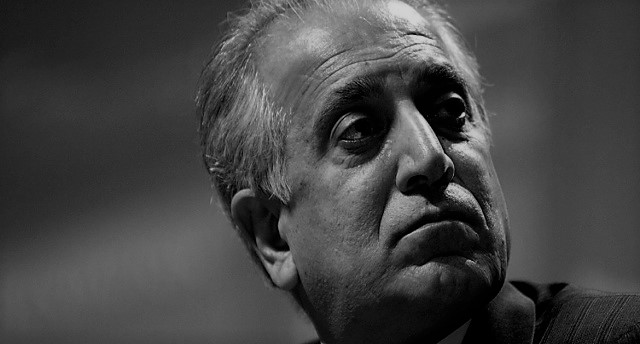

As per the plan, Zalmay Khalilzad is now in Kabul to take the Afghan government into confidence about these developments and would then fly back to Washington to seek approval from the US authorities. “Meetings here (in Doha) were more productive than they have been in the past,” Khalilzad tweeted without providing details. “We made significant progress on vital issues. We will build on the momentum and resume talks shortly. We have a number of issues left to work out”, he added.

He also mentioned in the tweets, that “[N]othing is agreed until everything is agreed, and ‘everything’ must include an intra-Afghan dialogue and comprehensive ceasefire”. The statement may present a gloomy picture about the outcome of the peace talks, along with highlighting complex mindset of Zalmay Khalilzad, but it also serves two purposes. It ensures not giving up entirely on the Afghan Taliban’ demands as well as placing the Afghan government in the peace equation.

Amid all these happenings, in another astonishing move, the Taliban appointed Mullah Baradar as the deputy of the Leader in Political Affairs and the Chief of the Political Office of the Islamic Emirate – which many see as a major reshuffle in Taliban’s Qatar political office.

Baradar was freed last year by Pakistan on the Afghan government’s request. Taliban’s spokesperson Zabihullah Mujahid said that the step was taken to ‘strengthen and properly handle the ongoing negotiations process with the US. The move is seen as a significant shift in Taliban’s peace talks approach as Baradar is considered, by many, as a senior leader with “credibility”. Plus, he is also perceived as a ‘dove’ in comparison to others in his ranks. Most probably, he will lead the Taliban side in next round of talks, once again in Doha, perhaps.

Not to forget, Pakistan has played a key role in bringing the Afghan Taliban to the dialogue table. Foreign Minister Shah Mahmood Qureshi on January 27, 2019, said that the negotiations between the Taliban and US is major diplomatic victory and more good news would be coming soon. Speaking to the media, he said: “[O]ur task was to bring the two parties to negotiating table and arrange the talks. Pakistan has achieved success on this front”.

He said Pakistan had always maintained that peace could not be achieved through war, adding that the international community had endorsed Pakistan’s viewpoint. The Minister said peace in Afghanistan was as important for Pakistan as for Afghanistan. “Being a neighbour and well-wishers, we support Afghanistan, and Pakistan has played its role too, but any decision about the future would be taken by Afghans themselves,” he reiterated.

However, it is important to remember here that the Taliban are negotiating from a position of strength. Unsurprisingly, to this point, talks have played out mostly how the insurgents have wanted them to play out: direct talks with the US, without Kabul, towards a troop withdrawal deal. Nonetheless, talks are not finished and it is yet to be seen how both sides use their bargaining power effectively, before signing off any written accord.

Though, worrisome part in the whole scenario is the exclusion of the National Unity Government (NUG) from the peace talks; Taliban have remained stubborn on this point and not talking to Kabul. How the Taliban and Kabul would respond to each other in near future, still needs to be decoded. As far as, Ashraf Ghani’s administration is concerned, things seem pretty much in control.

Pakistani PM Imran Khan and Afghan President Ghani’s in a telephonic conversation recently discussed efforts for peace and reconciliation in Afghanistan. Ghani expressed his gratitude for Pakistan’s sincere facilitation of these efforts, initiated by the US Special Representative for Peace and Reconciliation in Afghanistan Zalmay Khalilzad. PM Khan assured President Ghani that Pakistan was making sincere efforts for a negotiated settlement for the conflict in Afghanistan through an inclusive peace process, as part of its shared responsibility. This shows that the NUG and President Ghani are comfortable with peace talks, as long as they are being kept in the loop until a conclusive outcome.

In contrast, the Taliban should depute senior leaders for opening talks with those groups who would listen to them, separately, and could leave its staunch adversaries for later phase of the talks. It is also to be kept in mind that the upcoming presidential elections in Afghanistan may make any concessions more expensive, but on the positive side, the Afghan presidential candidates can sell peace for political mileage too. Now, it is on the pragmatism of Afghan leaders how they make use of this window of opportunity.

With that, a responsible US exit from Afghanistan would be one that attains a smooth transition from war to peace. At best, an election process likely delays such transition from taking place to the end of this year. In a worst-case scenario, another disputed election could make transition impossible as the country falls into a full-fledged political crisis. Therefore, two conflicting timelines must be reconciled: the six-month window Trump has apparently given Khalilzad to secure a deal with the Taliban, and the presidential elections scheduled for July. A sensible approach would be to stretch both timelines.

In conclusion, it can be cautiously said that the Afghan peace process is approaching the Nash equilibrium – a term used in the game theory to describe an equilibrium where each players’ strategy is optimal, given the strategies of all other players. A Nash Equilibrium exists when there is no unilateral profitable deviation from any of the players involved. No player in the game would take a different action as long as every other player remains the same. It is self-enforcing; when players are at a Nash Equilibrium, they have no desire to deviate because they will be worse off.

The author Saddam Hussein is a Research Fellow/Program Officer at Center for Research and Security Studies (CRSS), Islamabad. He graduated as a Development Economist from Quaid-i-Azam University (QAU) and also holds Master of Philosophy degree in Public Policy from Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE), Islamabad. He tweets @saddampide

© Center for Research and Security Studies (CRSS) and Afghan Studies Center (ASC), Islamabad.