Overview

Although al-Qa’ida (AQ) in Afghanistan and Pakistan has been seriously degraded, remnants of AQ’s global leadership, as well as its regional affiliate al-Qa’ida in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS), continued to operate from remote locations in the region that the group has historically exploited for safe haven. International, Afghan, and Pakistani forces continued to contest AQ’s presence in the region, and Pakistan’s continued military offensive in North Waziristan further degraded the group’s freedom to operate. Pressure on AQ’s traditional safe havens has constrained the leadership’s ability to communicate effectively with affiliate groups outside of South Asia.

Afghanistan, in particular, continued to experience aggressive and coordinated attacks by the Afghan Taliban, including the affiliated Haqqani Network (HQN) and other insurgent and terrorist groups. A number of these attacks were planned and launched from safe havens in Pakistan. Afghan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF) retained full responsibility for security in Afghanistan, and prevented the Taliban from capturing a provincial capital in 2016, although it suffered an unprecedented number of casualties in an intense fighting season. The ANDSF and Coalition Forces, in partnership, took aggressive action against terrorist elements across Afghanistan. A peace agreement between Hizb-e Islami Gulbuddin and the Afghan government in September was the first signed by an insurgent group since the 2001 fall of the Taliban.

While terrorist-related violence in Pakistan declined for the second straight year in 2016, the country continued to suffer significant terrorist attacks, particularly against vulnerable civilian and government targets. The Pakistani military and security forces undertook operations against groups that conducted attacks within Pakistan such as Tehrik-e Taliban Pakistan. Pakistan did not take substantial action against the Afghan Taliban or HQN, or substantially limit their ability to threaten U.S. interests in Afghanistan, although Pakistan supported efforts to bring both groups into an Afghan-led peace process. Pakistan did not take sufficient action against other externally focused groups, such as Lashkar e-Tayyiba and Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM) in 2016, which continued to operate, train, organize, and fundraise in Pakistan.

ISIS’s formal branch in Afghanistan and Pakistan, Islamic State’s Khorasan Province, remained active in 2016, although counterterrorism pressure from Afghan and U.S. Forces removed hundreds of fighters from the battlefield and restricted the group’s ability to control territory. Nevertheless, the group was able to conduct a number of high-profile, mass-casualty attacks in Kabul against sectarian and Afghan government targets. The group also claimed a number of mass-casualty attacks in Pakistan’s settled areas, likely conducted in collaboration with anti-Shia terrorist groups like Lashkar i Jhangvi.

India continued to experience attacks, including by Maoist insurgents and Pakistan-based terrorists. Indian authorities continued to blame Pakistan for cross-border attacks in Jammu and Kashmir. In January, India experienced a terrorist attack against an Indian military facility in Pathankot, Punjab, which was blamed by authorities on JeM. Over the course of 2016, the Government of India sought to deepen counterterrorism cooperation and information sharing with the United States. The Indian government continued to closely monitor the domestic threat from transnational terrorist groups like ISIS and AQIS, which made threats against India in their terrorist propaganda. A number of individuals were arrested for ISIS-affiliated recruitment and attack plotting within India.

Bangladesh experienced a significant increase in terrorist activity in 2016. Transnational groups such as ISIS and AQIS claimed several attacks targeting foreigners, religious minorities, police, secular bloggers, and publishers. Most notably, ISIS claimed responsibility for a July 1 attack on a restaurant in Dhaka’s diplomatic enclave, which resulted in 22 deaths. The Government of Bangladesh primarily attributed these attacks to domestic terrorists and political opposition.

People from Central Asia have travelled to Iraq or Syria to fight with militant and terrorist groups, including ISIS. Central Asians, like western Europeans, have been drawn to the fighting in Iraq and Syria for myriad reasons and fight on several sides. Central Asian leaders remained concerned about their involvement, but there was little evidence of Central Asian fighters returning home in significant numbers intent on attacking. Foreign terrorist fighters from Central Asian nations were suspected of committing attacks in third countries, however, including the June attack at the Istanbul, Turkey airport.

PAKISTAN

Pakistan remained an important counterterrorism partner in 2016. Violent extremist groups targeted civilians, officials, and religious minorities. Major terrorist groups focused on conducting terrorist attacks in Pakistan included the Tehrik-e Taliban Pakistan (TTP), Jamaat‑ul‑Ahrar (JuA), and the sectarian group Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (LeJ). Islamic State’s Khorasan Province (ISIS-K) claimed several major attacks against Pakistani targets, likely conducted in collaboration with other terrorist groups. Groups located in Pakistan, but focused on conducting attacks outside the country, included the Afghan Taliban, the Haqqani Network (HQN), Lashkar e-Tayyiba (LeT), and Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM).

The number of terrorism-related civilian deaths in 2016 was approximately 600, far lower than the peak years of 2012 and 2013, when terrorist acts killed more than 3,000 civilians each year (according the South Asia Terrorism Portal). Terrorists used a range of tactics – stationary and vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices (IEDs), suicide bombings, targeted assassinations, and rocket-propelled grenades – to attack individuals, schools, markets, government institutions, and places of worship. The Pakistani government continued to implement the national action plan against terrorism with uneven results. Progress remained slow on regulating madrassas, blocking extremist messaging, empowering the National Counter Terrorism Authority (NACTA), cutting off terrorist financing, and strengthening the judicial system. Despite its extensive security infrastructure, the country suffered major attacks, particularly in Balochistan.

The Pakistani military continued operations in Khyber and North Waziristan to eliminate anti‑state militants. Security forces in urban areas, including the paramilitary Sindh Rangers in Karachi, arrested suspected terrorists and interrupted plots. In the aftermath of a high-profile terrorist attack at a Lahore park, the Rangers were also called temporarily into southern Punjab for law enforcement operations against militant groups. Many commentators credited the military operations for the reduced number of terrorism-related civilian deaths in Pakistan.

The Pakistan government supported political reconciliation between the Afghan government and the Afghan Taliban, but failed to take significant action to constrain the ability of the Afghan Taliban and HQN to operate from Pakistan-based safe havens and threaten U.S. and Afghan forces in Afghanistan. The government did not take any significant action against LeT or JeM, other than implementing an ongoing ban against media coverage of their activities. LeT and JeM continued to hold rallies, raise money, recruit, and train in Pakistan.

The Pakistan government has not joined the Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS, although it designated ISIS as a terrorist organization in 2015. Police and security forces detained and killed a substantial number of ISIS-affiliated terrorists.

2016 Terrorist Incidents: There were numerous terrorist attacks throughout Pakistan in 2016. The following list includes the incidents with the largest number of casualties.

- On March 27, a suicide bomber killed at least 74 people at Gulshan-e-Iqbal Park in Lahore. JuA claimed responsibility for the attack.

- On August 8, a bomb killed at least 70 people at a hospital in Quetta where lawyers had gathered to mourn the assassination of a prominent lawyer. JuA and ISIS-K separately claimed responsibility for the attack.

- On September 16, a suicide bomber killed at least 36 people at a mosque during Friday prayers in the Mohmand Tribal District. JuA claimed responsibility for the attack.

- On October 24, three militants stormed a police training center in Quetta and killed at least 60 people with gunfire and suicide vests. A LeJ affiliate and ISIS-K claimed responsibility for the attack.

- On November 12, a suicide bomber killed more than 50 people at the shrine of Sufi saint Shah Bilal Noorani in Balochistan. A LeJ affiliate and ISIS-K claimed responsibility for the attack.

Legislation, Law Enforcement, and Border Security: The Government of Pakistan continued to implement the Antiterrorism Act (ATA) of 1997, the National Counterterrorism Authority Act, the 2014 Investigation for Fair Trial Act, and 2014 amendments to the ATA, all of which allow enhanced law enforcement and prosecutorial powers for terrorism cases. Special courts under the ATA hear terrorism cases. The law allows preventive detention against suspects.

Under the 21st amendment to the Pakistani Constitution, passed in January 2015, military courts were empowered to hear terrorism cases through 2016. The government reinstated the death penalty for terrorism offenses after the Peshawar school attack in 2014. In August 2016, the Pakistani Supreme Court rejected an appeal and approved 16 death sentences for terrorism handed down by a military court, the first ruling by the Supreme Court that addressed capital sentences by military courts.

Military, paramilitary, and civilian security forces conducted counterterrorism operations throughout Pakistan. The NACTA received a significant budget in July. The Intelligence Bureau has nationwide jurisdiction and is empowered to coordinate with provincial counterterrorism departments. The Ministry of Interior has more than 10 law enforcement‑related entities under its administration, although some are under the operational control of the military. Each province has a counterterrorism department within its police force.

While the counterterrorism and anti-crime operations of the paramilitary Rangers in Karachi led to reduced levels of violence in the city, the media published allegations that the Rangers also targeted certain political parties for political reasons. The Sindh provincial government agreed to extend the mandate of the paramilitary Rangers for counterterrorism and anti-crime operations for 90 days on October 17.

The Punjab Counterterrorism Department raided a religious minority Ahmadi organization in Rabwah on December 5, ostensibly acting under counterterrorism laws against hate speech.

The Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) is responsible for border control at airports, seaports, and some land crossings. The paramilitary Rangers are responsible for border patrol in Punjab and Sindh, while the Frontier Corps do so in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, the Federally Administered Tribal Areas, and Balochistan, with the help of provincial police and tribal militias. Pakistan collects biometric information at land crossings with its International Border Management Security System. Authorities had limited ability to detect smuggling via air travel. The Federal Board of Revenue’s Customs Service attempted to enforce anti-money laundering laws and foreign exchange regulations at all major airports, in coordination with the Airport Security Force and the FIA. Customs’ end use verification project managed the entry of dual-use chemicals for legitimate purposes, while attempting to prevent their diversion for use in IEDs.

The continuous military operations in Khyber and North Waziristan eliminated significant numbers of militants and removed safe havens for terrorist groups such as TTP. On September 1, the military’s head of public relations announced that more than 300 ISIS members had been arrested and claimed the group’s attempt to establish itself in Pakistan had been foiled. However, ISIS’s regional affiliate, ISIS-K, claimed subsequent attacks and authorities announced further arrests of suspected ISIS militants. On September 26, NACTA announced it had frozen the bank accounts of 8,400 individuals and was working to revoke their travel documents, based on their inclusion on the Schedule IV list of ATA for suspected ties to terrorism.

On December 5, a military court sentenced Naeem Bukhari to death for “heinous offenses related to terrorism.” Bukhari was the alleged planner of the 2002 murder of American journalist Daniel Pearl in Karachi, in addition to many other terrorist acts. However, officials told the media the criminal charges leading to the sentence did not include the Daniel Pearl killing. Law enforcement officials continued to pledge assistance in apprehending U.S. citizen fugitives in Pakistan, but the process was cumbersome, requiring the U.S. Department of Justice to hire private attorneys to work with Pakistani prosecutors to move cases forward.

The trial of seven suspects in the 2008 Mumbai terrorist attack remained stalled, with many witnesses for the prosecution remaining to be called by the court. The lead defendant, alleged LeT operational commander Zaki-ur Rehman Lakhvi, remained free on bail.

Specialized law enforcement units often lacked the equipment and training needed to implement the enhanced investigative powers provided by counterterrorism legislation. Interagency information sharing was sporadic with no integrated database capability. NACTA did not make significant progress in operationalizing the Joint Intelligence Directorate, intended to coordinate civilian and military counterterrorism information sharing. ATA courts moved slowly in processing terrorism cases due to the overly broad definition of terrorism offenses in the ATA. Some ATA courts attempted to transfer cases that were not terrorism-related back to the regular courts. Prosecutors had a limited role during the investigation of terrorism cases, and jurisdictional divisions among military and civilian security agencies hampered investigations and prosecutions, which sometimes also lacked sufficient evidence. Terrorist groups intimidated witnesses, police, victims, prosecutors, defense lawyers, and judges. All of these factors contributed to high acquittal rates in ATA courts.

The Department of State carried out some counterterrorism training in Pakistan, but had to conduct certain programs in third countries due to the government’s non-issuance of visas for trainers. In September, the Ministry of Interior cancelled all training inside Pakistan under the State Department’s Anti-Terrorism Assistance program.

Countering the Financing of Terrorism: Pakistan is a member of the Asia Pacific Group on Money Laundering, a Financial Action Task Force (FATF)-style regional body. Pakistan criminalizes terrorist financing through the ATA. However, there has not been a significant number of prosecutions or convictions of terrorist financing cases reported by Pakistan in recent years due to a lack of resources and capacity within investigative and judicial bodies.

In 2015, FATF removed Pakistan from its review process due to progress on countering the financing of terrorism (CFT). In October 2016, FATF noted concern among members that Pakistan’s outstanding gaps in the implementation of the UN Security Council ISIL (Da’esh) and al-Qa’ida sanctions regime had not been resolved, and that UN-listed entities – including LeT and its branches – were not being effectively prohibited from raising funds in Pakistan. Despite Pakistan’s CFT laws, its freezing of several relevant bank accounts from March 2015 to March 2016, and other limited efforts to stem fundraising by LeT, the group and its wings continued to make use of economic resources and raise funds in the country in 2016. Pakistan’s ban on media coverage also did not appear to reduce the ability of LeT to collect donations.

Pakistan’s national action plan includes efforts to prevent and counter terrorist financing, including by enhancing interagency coordination on CFT. Pakistan’s National Terrorists Financing Investigation Cell, operated by the Federal Investigations Agency, Federal Board of Revenue, the State Bank, and intelligence agencies, tracks financial transactions between the national and international banking systems. Additionally, NACTA coordinates with all relevant agencies to counter terrorism and terrorist financing.

The Anti-Money Laundering Act (AMLA) of 2010 designates the use of unlicensed hundi and hawala systems as predicate offences to terrorism and also requires banks to report suspicious transactions to Pakistan’s financial intelligence unit, the State Bank’s Financial Monitoring Unit. Although unlicensed hawala operators are illegal in Pakistan, these unlicensed money transfer systems persist throughout the country, especially along Pakistan’s border with Afghanistan, and were open to abuse by terrorist financiers operating in the cross-border area.

For further information on money laundering and financial crimes, see the 2017 International Narcotics Control Strategy Report (INCSR), Volume II, Money Laundering and Financial Crimes: http://www.state.gov/j/inl/rls/nrcrpt/index.htm.

Countering Violent Extremism: NACTA held a workshop with non-governmental organization (NGO) participation in July as part of the process of creating a National Counter Extremism Policy and aimed to finalize the policy by early 2017. The Ministry of Information and Broadcasting and the military’s public relations wing shaped media messages to build support for the military’s counterterrorism initiatives. The government operated de‑radicalization camps offering “corrective religious education,” vocational training, counseling, and therapy. A Pakistani NGO administered the widely-praised Sabaoon Rehabilitation Center in Swat Valley, which was founded in partnership with the Pakistani military and focused on juvenile violent extremists.

International and Regional Cooperation: Pakistan participated in the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation meetings on counterterrorism and in other multilateral groups where counterterrorism cooperation was discussed, including the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (as an observer), the Heart of Asia-Istanbul Process, and the Global Counterterrorism Forum. Pakistan participated in UN Security Council meetings on sanctions and counterterrorism.

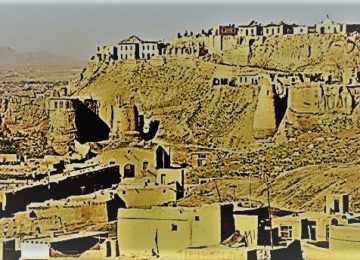

AFGHANISTAN

Primary responsibility for security in Afghanistan transitioned in January 2015 from U.S. and international forces, operating under the then NATO-led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) Mission, to the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF), while U.S. forces maintain the capacity to conduct counterterrorism operations in Afghanistan as outlined in the U.S.-Afghan Bilateral Security Agreement. In 2016, the majority of counterterrorism operations were carried out in partnership with, or solely by, Afghan forces. Additionally, the United States supported Afghan efforts to professionalize and modernize Afghanistan’s security forces through the contribution of almost 7,000 U.S. troops to the NATO Resolute Support Mission, a non-combat mission to train, advise, and assist Afghan security forces to improve their readiness and capabilities.

The fighting between the ANDSF and the Taliban throughout 2016 was characterized by the capture and recapture of facilities and territory by both sides, with the ANDSF maintaining control of major population centers – provincial capitals and the majority of district centers – while the Taliban gained or maintained control of substantial territory in less populated, rural areas (although it was able to regularly exert pressure on population centers), thereby creating an environment of persistent insecurity. Despite repeated sieges, the Taliban were unable to fully capture and hold provincial government capitals in Farah, Helmand, Kunduz, and Uruzgan. The Taliban, and the affiliated Haqqani Network (HQN), also increased high-profile terrorist attacks targeting Afghan government officials – including justice officials – and members of the international community.

ISIS’s radical and violent ideology, combined with larger payments to fighters and their families, attracted disaffected elements of insurgent and terrorist groups in Afghanistan, however, a vast majority of Afghans, including Afghanistan-based militants such as the Taliban, rejected ISIS’s ideology and brutal tactics. Islamic State’s Khorasan Province (ISIS-K) presence was primarily limited to some areas of Nangarhar and Kunar provinces. The ANDSF and U.S. counterterrorism operations killed hundreds of ISIS-K fighters, including ISIS-K leader Hafiz Saeed Khan in July 2016 in Nangarhar Province. On numerous occasions, Taliban and ISIS-K fighters clashed over control of territory and resources. ISIS-K conducted a number of high-profile attacks during the second half of 2016.

2016 Terrorist Incidents: Insurgents across Afghanistan used a variety of tactics to expand their territorial influence, disrupt governance, and create a public perception of instability. According to ANDSF statistics, ANDSF casualties were 30 percent higher in 2016 than in 2015. Insurgents continued to use large vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices (VBIED) and complex attacks involving multiple attackers laden with suicide vests working in teams to target ANDSF, Afghan government buildings, foreign governments, and soft civilian targets to include international organizations. Kabul remained a focus of high-profile attacks. Baghlan, Farah, Ghazni, Helmand, Kunar, Nangarhar, and Uruzgan were the most dangerous provinces for ANDSF and civilians. U.S. citizens and foreigners continued to be targeted in kidnapping operations.

High-profile incidents included:

- On January 4, the Taliban claimed responsibility for detonating a VBIED near U.S. facility Camp Sullivan in Kabul, destroying several buildings and damaging the outer wall.

- On January 20, a Taliban suicide bomber drove a car loaded with explosives into a minibus carrying employees of Afghanistan’s largest television network, Tolo TV. The blast killed seven Tolo employees and injured 25.

- On April 19, HQN attackers detonated a VBIED on a National Directorate of Security (NDS) compound adjacent to the International Zone housing foreign embassies, killing 64 people and wounding 347 Afghans. This was the largest terrorist attack in an urban area since 2001 in terms of overall casualties.

- On June 20, an ISIS-K member detonated a suicide vest next to a bus carrying Nepali security guards from the Canadian Embassy, killing 16 people.

- On July 23, an ISIS-K member detonated a suicide vest at a peaceful demonstration by the Hazara ethnic minority group in Kabul, killing 80 people and wounding 231 people.

- On August 1, the Taliban detonated a 3,000 pound VBIED at the Northgate Hotel in Kabul. One Afghan National Police officer died in the subsequent fighting.

- On August 8, two American University of Afghanistan (AUAF) professors, one American and one Australian, were kidnapped in Kabul while traveling in their vehicle.

- On August 24, three insurgents attacked the AUAF in Kabul, killing seven students, seven teachers, three police officers, and two security guards. At least 35 other people were wounded, and all three of the attackers were killed. No group claimed responsibility for this attack, although many alleged it was the Taliban.

- On September 5, a Taliban suicide bomber killed 30, including several senior security officials, and wounded more than 90 people when explosives were detonated near the Ministry of Defense.

- On October 11, three ISIS-K terrorists assaulted the Ziarat-e-Sakhi mosque in Kabul as Shia Muslims commemorated Ashura, killing 17 individuals and injuring 58 others.

- On November 10, insurgents attacked the German Consulate in the provincial capital of Mazar-e-Sharif. The terrorists are widely believed to have belonged to the Taliban or its HQN affiliate. Terrorists killed one civilian and wounded 35 people when they used a VBIED to penetrate the security wall at the consulate. No German nationals were wounded, although the Consulate was severely damaged and will not reopen.

- On November 12, an Afghan employee at Bagram Airfield detonated a suicide vest inside the base at the behest of the Taliban, killing three U.S. soldiers, two U.S. contractors and wounding 14 people (13 U.S. citizens and one Polish national).

Legislation, Law Enforcement, and Border Security: The Afghan Attorney General’s Office investigates and prosecutes violations of the laws that prohibit membership in terrorist or insurgent groups, violent acts committed against the state, hostage taking, murder, and the use of explosives against military forces and state infrastructure, including the Law on Crimes against the Internal and External Security of the State (1976 and 1987), the Law on Combat Against Terrorist Offences (2008), and the Law of Firearms, Ammunition, and Explosives (2005).

In early 2014, the Justice Center in Parwan (JCIP) at Bagram Airfield began adjudicating cases of individuals detained by Afghan security forces who were never held in Coalition Law of Armed Conflict (LOAC) detention. The JCIP is the only counterterrorism court in Afghanistan that has nationwide jurisdiction. Notable cases tried during 2016 included:

- Fazal Rabi, who was convicted of providing financial and logistical support to the HQN and the Taliban, while based in Pakistan. He was sentenced to 10 years confinement by the primary court on August 8. His case was awaiting an appellate court trial at year’s end.

- Shaiuqullah was arrested in connection with rocket attacks on Bagram Airfield, which resulted in the death of a U.S. Defense Logistics Agency civilian. Shaiuqullah was found guilty of the lesser charge of membership in a terrorist organization by the primary court on May 9. He was sentenced to three years’ confinement. The case was with the appellate court at year’s end, which has ordered the NDS and Afghan prosecutors to provide more direct evidence supporting the murder charge.

- Anas Haqqani, who was detained in 2014, was sentenced to death by the primary court on August 29 for recruiting and fundraising on behalf of the HQN. Anas is the brother of Sirajuddin Haqqani, the deputy leader of the Taliban. The case remained in the Afghan legal system at the end of 2016.

On several occasions, U.S. law enforcement agencies assisted the Ministry of Interior, NDS, and other Afghan authorities to take action to disrupt and dismantle terrorist operations and prosecute terrorist suspects.

Afghanistan continued to process traveler arrivals and departures at major points of entry using the Personal Identification Secure Comparison and Evaluation System (PISCES). The system has been valuable for Afghanistan’s law enforcement and counterterrorism authorities in investigative and analytical efforts, and has been successfully integrated with INTERPOL’s i‑24/7 system.

Afghanistan continued to face significant challenges in protecting the country’s borders, particularly in the border regions with Pakistan. The Afghan Border Police leadership has stated its numbers and weaponry are insufficient to successfully secure border areas where they face difficult terrain, logistical challenges, and a heavily armed and determined insurgency.

Afghan civilian security forces continued to participate in the Department’s Anti-Terrorism Assistance program, receiving capacity-building training and mentorship in specialized counterterrorism-related skillsets such as crisis response.

Countering the Financing of Terrorism: Afghanistan is a member of the Asia/Pacific Group on Money Laundering, a Financial Action Task Force (FATF)-style regional body. Afghanistan remains on FATF’s list of “jurisdictions with strategic deficiencies” (the “gray list”). Specifically, insufficient cooperation and lack of capacity among government agencies continued to hamper terrorist finance investigations in Afghanistan.

In 2016, the FATF called on Afghanistan to “provide additional information regarding the implementation of its legal framework for identifying, tracing, and freezing terrorist assets [and] continue implementing its action plan to address the remaining anti-money laundering/combating the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) deficiencies.” Afghanistan’s financial intelligence unit, the Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Center of Afghanistan (FinTRACA), a member of the Egmont Group of Financial Intelligence Units, expressed its intent to reach the FATF action plan milestones.

Terrorist financing is a criminal offense in Afghanistan. In 2016, the attorney general issued an order immediately freezing assets of individuals and entities designated under UN Security Council resolutions 1267 and 1988. The Afghan government distributes UN sanctions lists under the 1267 and 1988 sanctions regimes to financial institutions via a link on FinTRACA’s website. To ensure full compliance with international standards on asset freezing, FATF recommended increased awareness among various relevant authorities about its obligations under the country’s CFT law.

Afghan officials indicated that because al-Qa’ida, the Taliban, and terrorist organizations from the Central Asian republics transfer their assets person-to-person or through informal banking system mechanisms like the hawala system, it is difficult to track, freeze, and confiscate assets. On occasions when more formal illicit transactions have come to the attention of the Afghan government, either via FinTRACA or security agencies, these entities reportedly worked promptly to both freeze and confiscate those assets.

The country’s counterterrorist finance law considers non-profit organizations as legal persons and requires them to file suspicious transaction reports. Similarly, money services businesses (MSBs), like hawaladars (brokers who informally transfer money within the hawala system), are required to register with and provide currency transaction reports to FinTRACA. Although these reports are not always consistently filed, supervision of hawalas and other MSBs is improving. FinTRACA revoked 61 business licenses and imposed $45,000 in fines on MSBs in 2016 for failure to comply with anti-money laundering/counterterrorist financing laws.

For further information on money laundering and financial crimes, please see the 2017 International Narcotics Control Strategy Report (INCSR), Volume 2, Money Laundering and Financial Crimes: http://www.state.gov/j/inl/rls/nrcrpt/index.htm.

Countering Violent Extremism: Since taking office in 2014, President Ghani has actively engaged on countering violent extremism (CVE) efforts, requesting that the Ulema Council, the recognized scholars and authorities on Islam in Afghanistan, condemn insurgent attacks and issue calls for peace in mosques throughout the country. President Ghani and Chief Executive Officer Abdullah reached out in the beginning of their tenure (2014) to civil society groups to understand the challenges of violent extremism and explore ways to counter these challenges. In an effort to stem discontent, President Ghani also visited a number of prisons and detention facilities to address inmate complaints about poor conditions and inequitable clemency programs. Afghan religious leaders and government officials attended conferences at the Hedayah Center, an International Center of Excellence for Countering Violent Extremism in Abu Dhabi.

Since late 2015, the Afghan Office of the National Security Council (ONSC) has been working, with international donor support, to develop a national strategy to counter violent extremism. The ONSC created an inter-ministerial working group to develop and implement the strategy, and supported a series of provincial-level conferences on CVE designed to elicit feedback from provincial leaders on the best way to prevent and counter violent extremism in their communities. This feedback will be integrated into the final government strategy.

The lack of oversight over religious activities at mosques remained an issue as only 50,000 out of 160,000 mosques are registered with the Ministry of Hajj and Religious Affairs and the Ministry of Education. Weak regulation of religious institutions has led to a number of unregistered mosques with associated religious schools (madrassas) operating independently of the government.

While executing the fighting season campaign against the Taliban, President Ghani has simultaneously encouraged the Taliban and other insurgent groups to join a peace process. Supported by the United States and other members of the international community, the Afghanistan Peace and Reintegration Program (APRP), launched in 2010, was the government’s main tool for the implementation of peace activities, including the demobilization and reintegration of former insurgents, provincial-level peace outreach, engagement with the Ulema on CVE, and national-level reconciliation initiatives with senior Taliban leadership. Since its inception, the APRP claims to have reintegrated more than 11,074 former combatants, including 1,051 key commanders.

In 2016, the Afghan government transitioned away from the APRP towards a new, as yet unfinished project to create a broader Afghan National Peace and Reconciliation (ANPR) strategy. ANPR aims to: (1) promote reconciliation with insurgent groups; (2) build domestic and international consensus on the peace process; and (3) institutionalize a “culture of peace.”

The Afghan government signed a peace agreement with the Hizb-e Islami Gulbuddin (HIG) group in September, which was broadly supported by political groups. Successful implementation of the HIG agreement in 2017 and beyond, which was the first signed by an insurgent group after the fall of the Taliban in 2001, could set an example for other insurgent groups to follow.

Regional and International Cooperation: The Afghan government consistently emphasized the need to strengthen joint cooperation to fight terrorism and violent extremism in a variety of bilateral and multilateral fora. Notable among them is the Heart of Asia-Istanbul Process, in which regional countries have committed to counterterrorism cooperation. Afghanistan, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates lead the Counterterrorism Confidence Building Measure within the Process. The Afghan government also works closely with the UN Assistance Mission in Afghanistan and the United Nations Regional Center for Preventative Diplomacy for Central Asia to facilitate regional cooperation on a range of issues, including counterterrorism. Afghanistan is also an observer state within regional security organizations, such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and the Collective Security Treaty Organization; Afghanistan joined the Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS as its 66th member.

Source: Bureau of Counterterrorism and Countering Violent Extremism.

See full report here.