November 28, 2018

The Afghan Government and United Nations co-hosted the Geneva ministerial conference on 28 November 2018. This was the 13th high-level international conference on Afghanistan since 2001. The focus of the conference was peace efforts and development, but it was also an opportunity to assess the Afghan government’s reform efforts and reconfirm commitments made by donors to Afghanistan at the Brussels conference in 2016. Ahead of the conference, the AAN team answered some key questions regarding what will and will not be discussed at the event.

1. What is the Geneva conference about?

The Geneva conference is a non-pledging ministerial-level conference between the Afghan government and its international supporters. The conference will be co-hosted by the Afghan government and the UN, and will take place at the Palais des Nations, the UN headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland (for more details, see the Afghan Government’s official website on the Geneva conference and for an overview of the conference, see UNAMA’s website, here).

The main focus of the conference will be the peace effort and development.It will also be an opportunity for the government to present its track record on reforms and for the international community to reconfirm its commitments for development priorities until 2020. More specifically, the Afghan government will aim to show that it is on track with the implementation of the Afghanistan National Peace and Development Framework (ANPDF), the five-year strategic framework for self-reliance adopted in 2017. It will also need to show the progress made on the 24 commitments agreed upon at the 2016 Brussels conference, called the new Self-Reliance through Mutual Accountability Framework (SMAF) indicators or SMART deliverables (for the July 2018 progress reports see here and here), and, in particular, that it has delivered on most of the six commitments mutually agreed upon to be a minimum threshold for the Geneva conference. These were decided at a meeting of the Joint Coordination and Monitoring Board (JCMB) in July 2018 and included benchmarks such as holding parliamentary elections, which were held on 20 October but were marred by significant organisational shortcomings (the announcement of the final election results has been delayed once again and is now scheduled for the end of the year (see AAN dossier on elections preparations here and reporting on the elections here, here and here). The government will also need to show commitments made towards anti-corruption efforts (for the Afghan government’s progress, see the latest UNAMA report here, as well as the latest Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction – SIGAR – report here), as well as advances in security sector reform (see AAN reporting here and here). It will also need to show that it has met the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) benchmarks in macroeconomic stability, fiscal and financial reforms; that it has fostered private sector development; and worked towards the development of the ten National Priority Programs (NPPs).

According to the ANDF draft progress report prepared by the Afghan Ministry of Finance for the Geneva Conference, which AAN has seen, the Afghan government has, as of late October 2018, met “38 per cent of deliverables it set out had been fully achieved, with 45 per cent partially achieved.” The report said that the highest performing sectors were “justice sector reform, fiscal and economic reforms, growth through regional integration, public sector and civil service reforms and security sector reforms.”

The draft final report on the implementation of the 24 indictors agreed on at the Brussels conference (and seen by AAN) shows that, of these indicators agreed on in 2016, only 10 have been fully achieved, two are still in their initial phase and the remaining 12 have only either partially been achieved or only minor parts of a commitment have been achieved.

The two-day conference in Geneva will comprise a main event and a series of side meetings. It will start with a day of high-level side events (on women’s empowerment; private sector; people on the move; food security and livelihoods in times of drought) and four side meetings (regional connectivity and infrastructure; human rights; growth and development and counter-narcotics) on 27 November. This will be followed by four additional side meetings (anti-corruption; population dynamics; sustainable development goals (SDGs); Women Peace Process and NAP 1325, and the ministerial conference itself on 28 November. (For the agenda of the main event and an overview of side events and meetings, see here.)

On 28 November the Swiss and Afghan foreign ministers, Ignazio Cassis and Salahuddin Rabbani, will deliver the conference’s welcoming statement. Almost the entire morning part of the ministerial conference on 28 November will be dedicated to the topic of peace. The two key-note presenters here will be President Ashraf Ghani and UN Secretary-General António Guterres.

The rest of the day will be dedicated to presentations of the results from the side events and statements by regional and bilateral partners. There will also be feedback on the four side events held on 27 November focusing on the inclusion of women, economic development, migration, and climate change, the latter included in a session entitled ‘food insecurity in times of drought’. (The term ‘climate change’ itself will not be used, at least not in the programme, on the insistence of the US government, various diplomatic sources in Kabul have confirmed to AAN.) Key-note speakers for the first two events will be Rula Ghani, the Afghan president’s wife, who often takes on humanitarian issues, and Ashraf Ghani, respectively, while Chief Executive Abdullah will be the key note speaker for the last two events. The background documents of the side events provide a sobering reality check for the Ministry of Finance’s progress report. The background document on migration, for example, underlines that:

Afghans remain one of the largest displaced populations in the world with approximately 6 million Afghans residing in Iran and Pakistan; over 850,000 residing in the EU; and an estimated 2 million internally displaced. Afghan refugees constitute almost 15 per cent of the global refugee population and more than half of the 4.1 million refugees in protracted forced displacement of 20 years or longer.

The background document on food security and drought outlines the impact of conflict and climate change within Afghanistan:

Afghanistan is experiencing high – and rapidly rising – rates of food insecurity. The 2017 Afghan Living Conditions Survey (ALCS) found that 44.6 percent of the population is food insecure, an almost 12 percent increase from 2014. While conflict is a significant driver of this deteriorating situation, it is increasingly recognized that climate change is also having profound impacts on the food security of the Afghan population. […] In 2018, a major drought has left over 1.4 million people in need of urgent assistance. Given the country’s highly fragile ecosystems, the negative impacts will only increase over time, undermining agriculture, the leading economic sector, and contributing to displacement and continued instability, reinforcing the conflict.

It is relevant to note that the conference will be carried out mainly in English with translation into all six official UN languages at both the side events and the main conference on 27 and 28 November. According to the UN logistics document for the conference, “No interpretation will be available in any other language”. There will thus be no translation into either of Afghanistan’s two official languages. The same applies to the civil society event (more about this in part 4). The Afghan civil society organisations selecting their delegates for Geneva have therefore been requested to only send English speakers. This is problematic, as it excludes activists from the Afghan provinces where the operational languages are Dari and Pashto.

2. What are the expected outcomes of the conference?

While the Brussels conference in 2016 was a pledging conference, the Geneva conference will be focused on reviewing progress on commitments, as well as discussing policy and strategy. The formal outcomes of the conference are expected to be a Joint Communiqué and the renewal of Afghanistan’s commitments to international partners renamed as the Geneva Mutual Accountability Framework (GMAF).

A version of the draft communiqué seen by AAN takes note of the previous year’s “efforts to achieve peace” by the government, and includes an appeal from the signatories of the Joint Communiqué “to the Taliban and other parties to the conflict to embrace these opportunities for peace, especially the government’s offer to hold talks without preconditions.” Nasir Ahmad Andisha, Deputy Foreign Minister for Management and Resources, told Tolo news that the Geneva conference was about creating a ‘united definition of peace’ agreed on by international and regional actors.

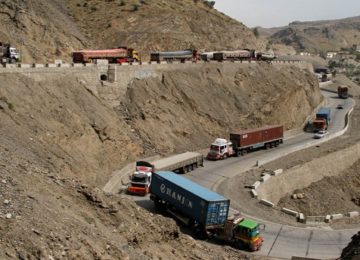

In the development section of the draft communiqué, the deliberations on Afghanistan’s economic development are put into a regional context. It emphasises “continued efforts by regional partner countries, organizations and mechanisms such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), the Heart of Asia – Istanbul Process, CAREC (Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation Program) and the Regional Economic Cooperation Conference on Afghanistan (RECCA).” It mentions “the establishment and expansion of air and ground corridors that facilitate products from Afghanistan accessing international markets, and other regional initiatives.” (1)

The Geneva Mutual Accountability Framework (GMAF) should be aligned with the ANPDF and the National Priority Programs (NPPs) and sets out measurable reform objectives for 2019-2020 (see here for the NPPs).

3. What were the previous international conferences on Afghanistan about?

The Geneva conference is the thirteenth high-level, international conference. Since the 2001 US-led intervention in Afghanistan, these conferences have usually been co-hosted by the Afghan government and changing international actors. This is the first time that no bilateral donor country has been ready to host the conference, according to multiple diplomatic sources in Kabul. The UN is therefore filling this gap. The EU, a major donor to Afghanistan, hosted the last conference.

The first international conference on Afghanistan was organised in Bonn in December 2001. There, Afghan and international representatives agreed on a road map for the re-establishment of permanent, democratically elected Afghan government institutions, the so-called Bonn Process. This process was to culminate in simultaneous presidential and parliamentary elections, to be held at the latest by June 2004. However, the presidential election was only held in October 2004, and the parliamentary elections had to be postponed for a year for organisational reasons.

In January 2002, the Tokyo conference on Afghanistan saw international donors pledge over 1.8 billion US dollars to rebuild Afghanistan, and over three billion US dollars for the years after (see AAN’s Kate Clark reporting here).

The Berlin conference on Afghanistan in April 2004 was supposed to mark the end of the Bonn Process, but participants were only able to note the “substantial progress” achieved since the Bonn Agreement of 2001, mainly the new Afghan constitution adopted at the 2003 Constitutional Loya Jirga (see an AAN account of this event here). Multi-year commitments were made for the “reconstruction and development” of Afghanistan, totalling 8.2 billion US dollars for the Afghan fiscal years 1383 – 1385 (March 2004 – March 2007), including a pledge of 4.4 billion US dollars for 1383 alone (March 2004 – March 2005).

In January 2006 at the London conference, the Bonn Process was formally declared successfully finalised. There, a first set of benchmarks were adopted based on what was called the Afghanistan Compact. This overarching conference document identified three areas of activities: security; governance, the rule of law and human rights; and economic and social development. Under each of these thematic areas, a number of benchmarks and target timelines were defined. Additionally, key principles of aid effectiveness were agreed on between donors and government, including to “increase the proportion of donor assistance channelled directly through the core budget, as agreed bilaterally between the Government and each donor” (see annex two of the Afghanistan Compact on pp 13 and 14, here). In April 2006, the Joint Coordination and Monitoring Board (JCMB), made up of the government of Afghanistan and its international supporters, was established and tasked with the strategic coordination and monitoring of the implementation of the Afghanistan Compact and the Interim Afghanistan National Development Strategy (IANDS).

In June 2008, at the Paris conference, co-hosted by the French and Afghan governments and the UN, international donors pledged an additional 21 billion US dollars to Afghanistan. The conference reaffirmed the Afghanistan Compact as the agreed basis for cooperation, as well as a new commitment to support the Afghanistan National Development Strategy (ANDS) for 2008-13.

In 2009, after the Den Haag international conference, co-hosted (as in Paris) by tripartite chairs, the communiqué emphasised that “effective, well-funded civilian programmes are as necessary as additional military forces and training programmes.” The participants agreed to significantly expand the resources and personnel devoted to civilian ‘capacity-building’ programmes, and pledged to improve aid effectiveness, in line with the June 2008 Paris Declaration.

In 2010, there were two major international conferences, in addition to the Lisbon NATO summit, where the plan for a phased handover of security responsibility from NATO and ISAF to the Afghan security forces (Inteqal)was announced.

At the 2010 London conference on Afghanistan, it was agreed that Kabul would gradually take over responsibilities for running the war and running the country over the following five years (see also previous AAN reporting). In July 2010, as had been agreed in London, the Kabul conference was held. There, ‘mutual progress’ on commitments was reviewed. Under the motto ‘Afghan-owned and Afghan-led’, President Karzai launched 22 National Priority Programmes grouped in six ‘clusters’ and asked for 15 billion US dollars in pledges (see also AAN previous reporting here; here; and here).

While new programmes and agreements have been negotiated ahead of every new conference, ‘progress’ has remained elusive, as noted by AAN’s Thomas Ruttig in 2010:

A glance at the recent international conferences exhibits vague and unknown progress, even by the rough statistics. For example, in 2006 the government of Afghanistan introduced the Afghanistan Compact at an international conference in London. The Afghanistan Compact was a comprehensive plan to address some of the basic and fundamental social development and governance priorities of the Afghan government and its people. However, right after two years of the Afghanistan Compact, another plan was introduced at the Paris Conference and that was the Afghanistan National Development Strategy. Again two years down the line, Afghanistan sees almost no significant signs of the implementation of the ANDS on the ground. It is worth mentioning, that the Comprehensive Strategy concluded at the Hague Conference last year too has remained unachieved so far.

In Lisbon, on 20 November 2010, the nations that contributed troops to ISAF issued a declaration (Lisbon Declaration on Afghanistan) announcing what they called ‘Afghanistan’s Transition’ – the gradual withdrawal of foreign forces and their replacement by Afghan ones. This transition to full Afghan security responsibility and leadership was to begin in early 2011 “following a joint Afghan and NATO/ISAF assessment and decision” and aimed to have the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) “lead and conduct security operations in all provinces by the end of 2014” (See also comments by AAN’s Thomas Ruttig ahead of the Lisbon summit here, a discussion of the phased handover here for an overview on NATO summits on Afghanistan see AAN reporting here.)

Nevertheless, 2010 marked the beginning of the so-called “process of transition,” which was to be completed by the end of 2014 and followed by a “transformation decade” (2015-2024). This was also a main message from an international conference held in Bonn in 2011, to mark the tenth anniversary since the first international conference on Afghanistan in 2001. Even the title of the conclusions from this conference “Afghanistan and the International Community: From Transition to the Transformation Decade” shows the spirit of a long commitment and two clearly defined processes that are in sequel to each other – from a military transition to a social and political transformation.

In July 2012, Afghanistan’s donors pledged 16 billion US dollars for the country’s economic and development needs at another international conference in Tokyo (see a UNAMA report here and rather more critical reporting by AAN here). The Tokyo pledges were made in response to the Afghan government’s strategy document, “Towards Self-Reliance”.This ambitious new strategy sought “sustainable growth and development” through the National Priority Programs (NPPs), focusing on economic growth, revenue generation, job creation and human development. The conference further agreed to a new set of benchmarks, known as the Tokyo Mutual Accountability Framework (TMAF).

Although, according to Afghan Ministry of Finance figures, 57 billion US dollars had already been disbursed in development aid between 2002 and 2010, with largely varying results, pledges and money continued to be given to a country with a very weak rule of law, virtually no mechanisms to control corruption and growing insecurity in large parts of the country. (For more details, see also AAN’s e-book Snapshot of an Intervention. The Unlearned Lessons of Afghanistan’s Decade of Assistance 2001–2011 and a recent SIGAR report Corruption in Conflict: Lessons from the U.S. Experience in Afghanistan.)

In December 2014, the tenth international conference on Afghanistan was held, again in London. This time the then-new Afghan president, Ashraf Ghani, presented a new reform programme entitled “Realizing Self-Reliance: Commitments to Reforms and Renewed Partnership”. The conference was not an explicit pledging event. Moreover, the National Unity Government had not been able to do much by that point, as it had been unable to agree on its cabinet. The conference communiqué thus simply stated that “the International Community reiterated its commitment, as set out in the Tokyo Declaration, to direct significant and continuing but declining financial support towards Afghanistan’s social and economic development priorities through the Transformation Decade.” (See AAN reporting on the London conference here). Ghani’s government at the Senior Officials Meeting held in September 2015 introduced a new document, the “Self-Reliance through Mutual Accountability Framework” (SMAF), which consolidated both its new reform agenda and the previous TMAF benchmarks, laying out a set of 39 benchmarks.

In October 2016, the European Union (EU) and the Afghan government co-hosted the Brussels conference (see AAN’s dispatch here). The conference resulted in the endorsement of and continued commitment to the three pillars of the Afghan government’s programme for the transformation decade (2015-2024). These included a commitment to an Afghan-led state and institution-building as outlined by the Afghanistan National Peace and Development Framework (ANPDF) and as measured by 24 indictors agreed upon in the new Self-Reliance through Mutual Accountability Framework (SMAF), called SMART SMAF (see here and here). The donors also committed to sustain international support and funding at or near current levels through 2020 with increased aid effectiveness. The third commitment included regional and international support for a political process towards lasting peace and reconciliation.

International donors pledged a total of 15.2 billion US dollars to support this agenda. The Geneva conference is an opportunity to review progress and commitments made at the Brussels conference.

4. What is the role of civil society at the conference?

Ten civil society delegates (half of them women – see the list and bios here) will participate in the high-level side events, the side meetings and the main Geneva Conference. This resembles the practice of previous conference. (2)

The Civil Society Working Committee (CSWC), a composition of the main umbrella civil society organisations, in cooperation with the co-hosts of the Geneva Conference identified, interviewed and selected the delegates. For developing their position paper, the Afghan civil society organisations held focus group meetings at the provincial level to collect civil society activists’ opinions. The result was discussed in a two-day national conference in Kabul on 11 and 12 October. This process was technically supported by the advocacy and networking organisation, the British and Irish Agencies Afghanistan Group (BAAG). Two of the delegates, one woman and one man, will present this position paper at the main conference on 28 November.

In addition to this, a one-day civil society event will be held on 26 November in Geneva, organised by BAAG. The event is envisaged as a series of working group discussions, which should determine key civil society requests from the donor community and government related to governance (elections, anti-corruption); security and peacebuilding; civic space; humanitarian issues (drought, people on the move); service provision (livelihoods, education, health) and gender equality and rights. Representatives of the donor community and the Afghan government are expected to join the civil society event in the afternoon of 26 November, when BAAG will present to them the key requests defined in the six working groups’ discussions.

Two of the civil society activists at the Geneva conference – one who will be the spokesperson for the ten official civil society delegates, the other will participate on behalf of his organisation outside the delegation – told AAN that, apart from one meeting with the Ministry of Finance, the conference organiser on behalf of the Afghan government, there was no prior consultation with the government. Naim Ayubzada, the spokesperson said that the meeting that took place on 16 November consisted of a briefing about the conference and was merely “symbolic.” He said that prior to earlier conferences, the government had consulted a broader array of civil society organisations based in Kabul, including those that did not have delegates. Ayubzada did not believe that their inputs would be included in the official conference documents. Abdullah Ahmadi, the chairperson of the Civil Society Joint Working Group who will travel to Geneva as one of several other organisations’ representatives participating on behalf of this group, confirmed that the government did not seek consultations with those groups

5. What difference do such conferences make?

Seventeen years since the international military intervention in Afghanistan and 12 conferences later – almost one conference every year and a half – progress in Afghanistan remains elusive. The Taleban control growing swaths of the country (see the latest SIGAR report); the government-run basic services, such as education and health, have been rife with corruption, and the population’s access to them has become more difficult due to the security situation (see AAN reporting here; see this MEC report about corruption in the Ministry of Public Health from June 2016 here; see also this SIGAR report on corruption in the health sector).

The Geneva conference, nevertheless – like the previous 12 high-level, international conferences on Afghanistan – will provide an opportunity to show donor governments’ and international organisations’ continuing commitment to Afghanistan and Afghans. Although this is largely symbolic, it is a chance to obtain public and media attention for a conflict that has increasingly dropped from the centre stage of world politics, although it continues to escalate (see this AAN analysis). With the Syrian war partially subsiding, Afghanistan is possibly becoming, once again, the most violent conflict worldwide (see this ICG quote) and a country whose population’s majority still lives beneath the poverty line.

The conference will also provide an opportunity to scrutinise the ever-changing indictors by which progress is measured, whose changes are often a question of semantics, but which always describe the same desired outcomes – less corruption, more peace, better security and governance. (See also this 2012 AAN report about “NATO’s effective abandonment of a conditions-based approach in implementing the [security] transition” – a phenomenon also witnessed in the tacit dropping or revising of agreed benchmarks in other fields).

For a few weeks, once again, Afghanistan will not only be the focus of diplomatic missions in the country and Afghanistan desks in capitals, but background briefs and speaking points will be read and edited at the highest levels of government and international organisations. This is also why the most important part of the Geneva conference will be the preparatory phase: the many meetings between the co-chairs about the what is on the agenda and what is not, preparing preliminary drafts of outcome documents and smoothing out possible diplomatic hiccups or crises in advance.

The outcome of an international conference like this will depend on how well it is negotiated before it begins. Realistic outcomes that all key actors can agree on are more likely to be implemented and easier to monitor. This is also why it is important that civil society – in all its varied forms – have an input throughout the process. Their delegates can also cut through diplomatic formulas and clearly point out the miseries the Afghan people continue to face. They did this, for example, at the December 2011 ‘Bonn 2’ conference, where, as AAN reported, the two civil society representatives that were allowed to address the main governmental plenum (of a delegation of 34) delivered “the strongest message of the day“ (our report here; unfortunately the link to their full speech, on the Afghan president’s website, is broken now). (3)

The failure to have a broader and topical consultations process with civil society organisations across the spectrum, not simply limited to Kabul, indicates that civil society involvement in such conferences remains largely formalistic. Consigning them to side events, and only allowing them a short statement and inclusion in the photo opportunity at the end is far from sufficient.

(1) This includes “the [two regional electricity transmission systems, the planned first phase of an integrated regional energy market in East, Central and South Asia]CASA [Central Asia-South Asia]-1000, TUTAP (Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan power project), the groundbreaking [sic] of the Afghanistan segment of the TAPI gas line, and the signing of the [Afghanistan-Black Sea] Lapis Lazuli Corridor Agreement, and the Trilateral Trade and Transit Agreement on Chabahar were conceded top priorities of the government of Afghanistan for achieving self-reliance.” (For news on the Lapis Lazuli Corridor Agreement, see here).

(2) Here are references to civil society in the documents from previous conferences:

We recognize the role of civil society and media in Afghanistan’s development and the need to include civil society in the political processes. We welcome the Afghan civil society’s contributions to the Conference and recognize also the contributions of international NGOs, both for Afghanistan’s development and in partnership with Afghan civil society, including in the provision of humanitarian assistance.

The Participants recognised the important role Afghan civil society has played in Afghanistan’s development. The Participants welcomed the Afghan Government’s commitment to the constructive, on-going dialogue with civil society, including Afghan women’s organisations, to ensure Afghan civil society’s full and meaningful involvement in key political processes, strengthening governance and the rule of law, as well as the development, oversight and monitoring of the refreshed TMAF. The Participants also noted the importance of protecting and strengthening free media. The Participants acknowledged the Afghan civil society statement at the Conference and welcomed the outcomes and conclusions of the Afghan civil society-led “Ayenda” associated event on 3 and 4 December. The Participants also noted the role that international NGOs play in development in Afghanistan as well supporting Afghan Civil Society and recognised as important their traditional role in humanitarian assistance in the future.

The Participants took note of the statement by Afghan civil society organizations at the Tokyo Conference. The Participants also welcomed the results of the civil society event jointly organized by Japanese and Afghan NGOs on July 7 in Tokyo.

The Kabul Process is to include annual meetings between the Afghan Government, the international community, and civil society, including those providing services, to promote norms and standards for mutual accountability.

(3) It is worth re-reading AAN’s reporting from this conference, as it will become apparent how similar problems discussed there are to those still on the agenda in 2018, speaking for a lack of progress made over those years. On the civil society forum, here and here, on the main conference here and here.

By Special Arrangement with AAN. Original link.

Disclaimer: Views expressed on this blog are not necessarily endorsed or supported by the Center for Research and Security Studies, Islamabad.