2001 – 2003: Building the Foundations for the ANDSF

On 9/11, the U.S. military had no plans prepared and readily available for operations in Afghanistan. As a result, the U.S. response was initially led by Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) operators, leveraging intelligence assets and personal relationships with anti-Taliban militias, mainly the Northern Alliance faction. Department of Defense (DOD) planners focused on kinetic operations and had little time to plan for post-conflict reconstruction, including building a national army and police force.

By 2002, the United States and its coalition partners had concluded that developing and training a professional Afghan national security force could serve as a viable alternative to an expansion of international forces in Afghanistan. Despite agreeing to lead the development of the new Afghan army, the United States lacked an active and readily available military force, interagency doctrine, or model for reconstructing a foreign military at the scope and scale required.

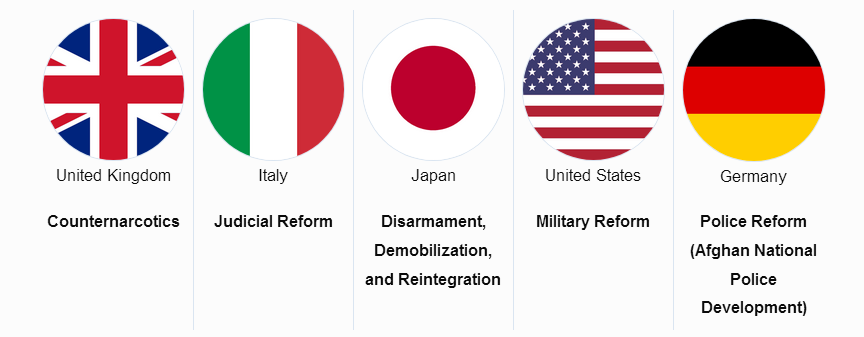

In April 2002, the Group of Eight (G8) nations met to map out divided responsibilities for security sector reform in Afghanistan. Five independent silos with an appointed lead nation were created.

Lead Nations of Security Sector Reform in Afghanistan

U.S. training of the new ANA began with the deployment of U.S. Special Forces to lead the effort. Eventually recognizing that training a national army was beyond the core competency of the Special Forces, the United States deployed U.S. Army conventional forces to expand the training program from small infantry units to larger military formations, and to develop defense institutions. To ensure sufficient U.S. combat support for the 2003 invasion of Iraq, the Army National Guard assumed responsibility for ANA training.

2004 – 2008: Rapid Expansion of the Force to Address Growing Insecurity

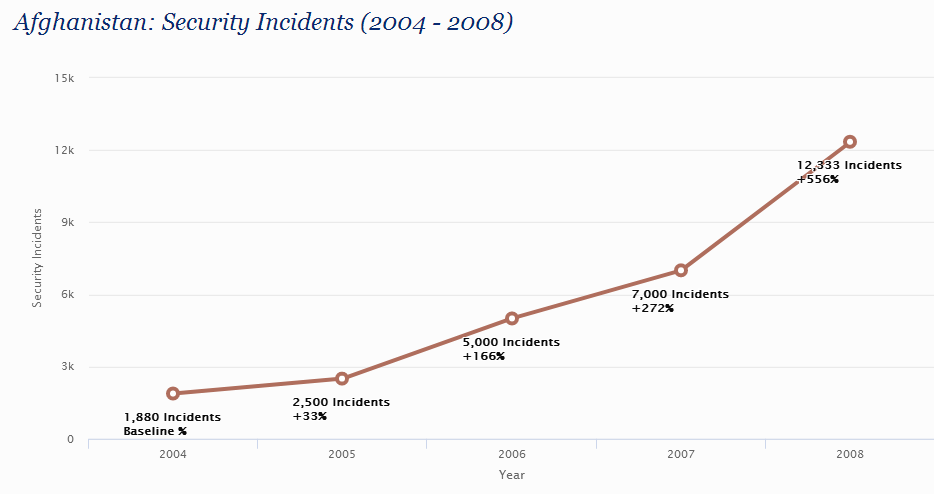

In 2004, the United Nations described the security situation in Afghanistan as “volatile, having seriously deteriorated in certain parts of the country.” The United States recognized that dividing security sector responsibilities among the coalition had not produced the desired results, requiring the Bush administration to increase U.S. commitments. DOD expanded its role in police development efforts and assumed responsibility for the coordination, training, and advising of both the ANA and Afghan National Police (ANP).

Note: Numbers on graph indicate the total number of security incidents recorded that year. Incidents include suicide bombings, indirect attacks, improvised explosive device (IED)/mine incidents, IED/mine direct attacks, and direct attacks.

Source: Defense Intelligence Agency, “Afghanistan Security Incidents Database: 15 April 2016.”

To counter rising violence and instability, the United States pushed to expand the ANP from 60,000 to 82,000 and the ANA from 75,000 to 134,000. As part of the expansion, the United States initiated training of specialized units, transitioning the ANA to a combined arms service with army, air force, and special forces elements.

Because the Afghan Air Force (AAF) was not initiated until 2006, combat aviation capabilities were slow to get off the ground. Conversely, the Afghan Special Forces showed high morale and retention rates, and benefited from close, long-term relationships with U.S. Special Forces trainers, better living conditions, and higher pay than their conventional force counterparts.

The United States also initiated three specialized police programs which—with limited oversight from and accountability to the Afghan and U.S. governments—were reported to have engaged in human rights abuses, drug trafficking, and other corrupt activities, ultimately serving as a net detractor from security.

The decision to expand the ANDSF was made without considering the associated fiscal and resource requirements, creating dramatic shortfalls in funding and leaving the train, advise, and assist mission chronically understaffed. Inadequate infrastructure, equipment, and recruitment further undermined ANDSF force readiness, and the creation of increasingly complex and expensive security institutions delayed prospects for sustainability and Afghan ownership.

2009 – 2014: U.S. Surge and Transition

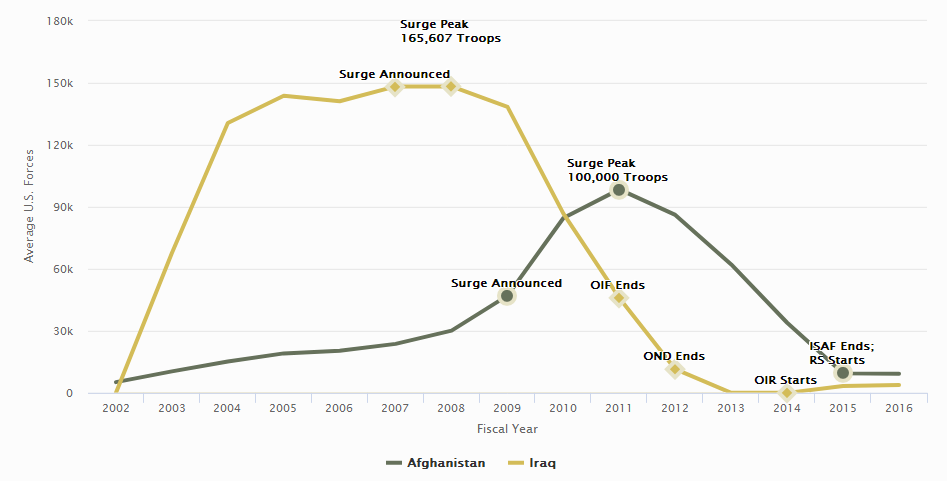

In 2009, with the Taliban threat increasing and the ANDSF struggling to secure the country, President Obama authorized a surge of U.S. combat forces, agreed to increase ANDSF end-strength, and pursued a strategy of rapidly improving security while supporting the development of the ANDSF. This dual-track strategy resulted in an environment ripe for capacity substitution, where U.S. trainers and advisors augmented critical gaps in Afghan capability, providing enablers and leadership to ensure success on the battlefield.

In November 2010, participants at the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) Lisbon Conference formally agreed to a process through which the ANDSF would assume lead security responsibility from international forces by the end of 2014.

Guided by the prevailing U.S. counterinsurgency (COIN) strategy, the United States armed and employed the ANP in COIN operations. The increased militarization of the force led to the underdevelopment of civil policing functions. The resulting inability of the government and police to effectively respond to criminal actions created an opportune environment for Taliban exploitation.

Average U.S. Forces in Iraq and Afghanistan, FY 2002 – FY 2016

Note: Charted operations include Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF), Operation New Dawn (OND), Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR), International Security Assistance Force (ISAF), and Resolute Support (RS). For FY 2002–2007, the annual total is derived from average monthly troop levels. For FY 2008–2016, the annual total is derived from average quarterly troop levels. While the 2007 total (from monthly averages) in Iraq was 148,300 troops, troop levels surged to 165,607 in the fourth quarter. U.S. troop numbers in Iraq for FY 2012 (11,445) represent the number of troops in the first quarter; there were no U.S. troops in Iraq by the end of the second quarter beyond a residual force that remained to provide embassy security and other security cooperation assistance. Starting in June 2014, additional U.S. military personnel were sent to Iraq in OIR to advise and train Iraqi forces and support U.S. military operations against the Islamic State.

The assessment tools used by the United States and its coalition partners to evaluate the ANDSF focused on tangible information, such as training and equipment, and failed to assess intangible but important factors, such as corruption and leadership. Furthermore, these assessment tools created disincentives for Afghan units to improve because the coalition prioritized supporting units with lower ratings.

Without accurate assessments of ANDSF capabilities, and with coalition forces augmenting the ANDSF, it wasn’t a surprise that as U.S. and coalition forces drew down, the ANDSF struggled to succeed.

2015 – 2016: Train, Advise, and Assist

Following the official transition of security responsibilities from U.S. and coalition forces to the ANDSF, attrition, casualties, and the issue of “ghost soldiers’” heavily undermined ANA force strength. Furthermore, friction among contributing nations about the role of the ANP resulted in an identity crisis, and the persistent focus on unsustainable force numbers over professionalism has left the ANP with significant deficiencies.

The Afghan Special Forces became the “best-of-the-best” in the Afghan military. However, because conventional forces suffered from high attrition and serious deficits in training, equipment, and readiness, the Afghan Special Forces increasingly filled the void, resulting in overuse of the force.

It was not until 2015 that the United States and coalition prioritized security sector governance and defense institution building in concert with improving the fighting capabilities of the force. Even with these efforts, corruption within the security forces and associated ministries threatened ANDSF readiness and battlefield performance.

As security has continued to deteriorate, force protection requirements have increased, ultimately restricting U.S. advisors’ ability to operate. Afghan President Ashraf Ghani is currently attempting to restructure the ANDSF to optimize offensive capabilities and to reverse the eroding stalemate, but with the U.S. military presence confined to large military bases in major population centers and the civilian advisory mission largely stuck behind U.S. Embassy Kabul’s walls, there are limits on what can be achieved.

Source: SIGAR Website, September 2017.