The coup d’etat that brought the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) was a watershed for Afghanistan, driving it into a conflict from which it has yet to recover and ushering in a whole new level of violence by the state against its citizens. Forced disappearances, the routine use of torture for punishment as well as to gain confessions, and massacres of civilians all marked the bloody period from 27 April 1978 until 24 December 1979 when the Soviet Union invaded. The veteran Human Rights Watch Afghanistan expert, Patricia Gossman*, here looks at those crimes and their legacy.

This is the third part of a mini-series looking at the Saur Revolution and its consequences. Part 1 looked at what happened and why there was a coup. In Part 2, we presented the stories of eight Afghans who were alive at the time, their memories of the day itself and the impact the coup had on their lives. Part 4 will examine the relationship between the PDPA and the Soviets after the Soviet invasion of December 1979.

In 1978, there was no Twitter or Facebook to spread the news. Reporting from India a day after the events, the New York Times described the coup as “bloody and violent”, but information on the atrocities that unfolded over subsequent months trickled out very slowly. There were few journalists and no human rights groups on the ground to document what happened. This may be one reason why, even today, it comes as a surprise to many people to discover that serious war crimes in Afghanistan did not begin with the Soviet invasion of December 1979, but 20 months earlier.

While neither the Daud regime, nor the government under Zahir Shah were noteworthy for respecting human rights, growing demands for greater political openness had produced a number of reforms. They were limited and often short-lived, but there was some measure of free speech and freedom of assembly. In April 1978, the PDPA party leadership under Nur Muhammad Taraki and Hafezullah Amin killed President Daud Khan and most of his family and then embarked on an ambitious, but ill-planned effort to transform Afghanistan virtually overnight into a modern socialist state. The violence perpetrated by the state was extreme, indiscriminate and widespread

(For a detailed account of the political dynamics in the years leading up to the coup, see AAN’s earlier dispatch.)

Unprecedented Violence: Secret Executions and Forced Disappearances

Taraki launched the coup as what he called a short cut to “the destiny of the people of Afghanistan.” (1) The fact that the Khalqis had virtually no support base outside their immediate membership partially explains the extreme violence of the months following the coup. Amin (who had studied at the University of Wisconsin and Columbia University in the 1960s where he was exposed to leftist student politics) was the driving force of the campaign. Taraki, his mentor, called the Khalqis “the children of history,” which according to scholar, Anthony Hyman, illustrated “the almost messianic faith shared by many Khalqis that they had a special role to play as agents of modernisation in Afghanistan.” (2) It was clear that Amin saw himself in that role.

To carry out this sweeping transformation, the Khalq leaders set about eliminating all political rivals and those they considered to be obstacles to their efforts to transform the Afghan state, including anyone who had served in the governments of Zaher Shah and Daud, mullahs, pirs and other religious elites, tribal leaders, Maoists and other leftists outside the PDPA, professionals of every kind and other members of the educated class other than those who had joined the Khalq party and the leaders of various ethnic communities. Abandoning the brief rapprochement with Parcham, the other faction of the PDPA, Taraki and Amin purged the party of leading Parcham members, executing at least hundreds, imprisoning others and exiling some as ambassadors abroad.

American scholar Louis Dupree, who was living in Kabul at the time of the 1978 coup, spoke of “thousands” being arrested from all targeted groups in Kabul alone in the months after the coup, (3) the vast majority of whom were secretly killed. In most cases, the families never received the bodies for burial or any official acknowledgement of their deaths. Many were killed inside Pul-e Charkhi prison and buried in mass graves there. General Nabi Azimi, a Parchami who would become deputy defense minister and commander of the Kabul garrison under Najibullah, wrote that the regime “arrested too many ordinary people, clergymen, intellectuals … and put them in Pul-e Charkhi prison or executed them … without trial on dark nights and threw them into holes already prepared.” (4) Amnesty International reported in 1979 that it had “received a substantial number of allegations that political prisoners [were] … subjected to torture. … some prisoners [were] paralyzed and that others died as a result of torture.” (5) The prison was vastly overcrowded with some 12,000 prisoners in 1979. (6) Many died from disease from poor food and sanitation.

In 1986, scholar Olivier Roy suggested that throughout the country in those 20 months, between 50,000 and 100,000 people were forcibly disappeared, saying then that “the story of this wave of repression has yet to be written.” (7) It remains a largely untold story, although the few available accounts give a sense of the scale of killing. Dr Sima Samar, chair of the Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission, said of the time: “Any Khalqi could kill anybody.” (8) Some accounts of people whose relatives remain disappeared and mourned to this day can be found in AAN’s oral history of the ‘Saur Revolution’, here.

A UN report mapping the major patterns of human rights violations from the war’s beginning was meant to be published in January 2005, but was deemed too sensitive for official release (see AAN analysis here). It included this description:

[T]he regime … tortured captives not solely as an interrogation tactic, but to humiliate, punish, and annihilate them … The tortures and executions in Pul-i Charkhi prison became part of the legends of this time, which form part of the Afghan national memory.

The new intelligence agency Taraki had created, Da Afghanistan Gato Satonki Idara (AGSA) (in Pashto, the Administration for the Protection of the Interests of Afghanistan) was principally responsible for carrying out the arrests and executions. It was headed by Assadullah Sarwary. President Taraki set the tone for its operations, announcing in March 1979, “Those who plot against us in the dark will disappear in the dark.”(9) Sarwary remains the only former PDPA official from this period to ever face trial in Afghanistan. Taken into custody by Shura-ye Nazar forces when they entered Kabul in April 1992, Sarwary was detained in Panjshir until he was brought to Kabul in 2005. In February 2006, he was tried in a rushed proceeding, found guilty of conspiracy against the state and mass killings and sentenced to death. An appeals court reduced the sentence to 20 years. Sarwary was released in January 2017. (See AAN reporting here)

Resistance and Repression in the Provinces

The tactics used by the Taraki-Amin government to crush any opposition sparked resistance throughout the country. The Herat uprising was the largest such challenge to the regime at the time, demonstrating the extent of popular resistance even in the cities. In March 1979, military commanders, including Ismael Khan, mutinied and began providing arms to resistance fighters in Herat city. They held the city for a week before the government, with the support of Soviet bombers, crushed the rebellion, killing possibly several thousand people. According to the Afghanistan Justice Project, the dead were buried in mass graves between Takht Saffar and Bagh-e Millat, an area locals thereafter called the area “the place of obscure martyrs.” (10)

The Khalq government also relied on violence to impose its reform agenda outside the cities. In an incident described in the 2005 Afghanistan Justice Project report, local authorities called the men of a Kandahar village in Dand district to come to the village school, and then asked the assembled villagers to identify the local landlords and any others resisting land reform measures. Those so identified were taken away. One witness described the scene:

Then they asked, “who has said women should wear the chador?” Again, some admitted saying it, and others were accused of doing so by some in the crowd. They were taken away too. Then those who had been accused were put into three big trucks and taken to the governor’s office. The relatives came there searching for their men. In the evening 29 of them were killed. Some were released, and others remained there. My brother was held there, and for a time we could bring him food. When Amin came to power [in September 1979], the prisoners were taken away and we never saw them again. (11)

The regime undertook military operations—which involved mass arrests and summary executions—in areas where resistance was strongest. Kunar was one such area. In early 1979, organized resistance to the PDPA had gained considerable ground throughout the province. By March the mujahedin had captured all the district centres, and were launching sustained attacks on the provincial capital, Assadabad. The besieged provincial personnel requested military assistance from Kabul, which deployed the 444 Commando Force commanded by Sadeq Alamyar. (12) His forces trapped some of the retreating mujahedin within Assadabad’s outskirts, in particular the village of Kerala, and moved in for a clean-up operation that included reprisals against the local population. The troops summoned all the men and older boys to an area of open ground on the river bank, next to the bridge which links Kerala to Assadabad. They then opened fire, and afterwards used a bulldozer to dig a trench to bury the bodies. The main mass grave is still visible in this location. (13)

In October 2015, the Netherlands police arrested Alamyar in Rotterdam, where he had been living since the early 1990s, as a suspect in the mass killing of men and boys in Kerala on 20 April 1979. According to the official statement, Dutch police made the arrest on the basis of a criminal complaint by relatives of those killed. The statement alleged that Alamyar had been head of a commando unit that had “dragged large numbers of men and boys from their homes and … killed them.” (See AAN reporting on the announcement here) The statement included a call for:

[P]ersons who were present in or around Kerala, Dam Kelai or Assadabad on or around 20 April 1979 and who are witnesses of events relating to the investigation to contact the Netherlands National Police. Persons who were present at the time as government troops or government officials may have information that is especially important for the Dutch investigation. These categories of persons are therefore urged to provide such information to the Dutch Police.

Alamyar was released from custody, although the investigation remains open, pending any additional information coming to light.

The Kerala massacre was the largest mass killing of the early years of the war. Indeed, that record would remain until the late 1990s when Jombesh and Hezb-e Wahdat forces in and around Mazar-e Sharif and Dasht-e Laili killed over 3000 Taliban prisoners in May-June 1997 and then, a year later, when the Taleban killed thousands of civilians, mainly Hazaras, after they captured Mazar in August 1998.

The Legacy: Cycles of Violence

After the Soviet invasion in December 1979, the new regime attempted to count the missing, but gave up as the numbers climbed over 25,000. (14) Five years ago, the Dutch government published an official listof 5000 names it had obtained in the course of an investigation into a war crimes suspect—a ‘death list’ of those detained and marked for execution at the time (see AAN reporting here). It was the only official acknowledgement any families ever received, but it represented a small fraction of those who were killed. I recently discussed this period with an Afghan journalist who grew up listening to stories about his grandfather, who was detained and tortured after the coup, and others who were among the disappeared. He lamented how few of his peers in Afghanistan know the history of those early years, though they live with its legacy in a conflict that continues to this day.

The PDPA’s reforms and the brutal way it imposed them launched a resistance movement that included people from a wide spectrum of Afghan society. As widespread repression prompted mutinies in army garrisons across the country, the imminent disintegration of the armed forces ultimately prompted the Soviet Union to invade to prevent the pro-Soviet state from collapsing.

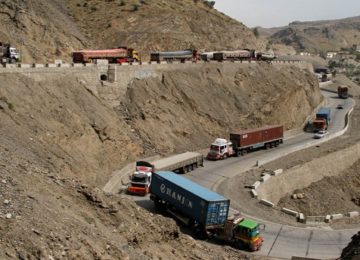

Millions of Afghans were then displaced inside the country and millions more fled to Iran and Pakistan as refugees, a pattern of forced migration echoed many times over the next few decades as war washed over lands, villages and cities. The forced mass migration in the early 1980s fractured social ties which had already been weakened by the PDPA’s killing of many traditional leaders. As armed resistance mounted, authority increasingly belonging to commanders, those who could win the loyalty of armed fighters. Their power and influence has remained to this day: because of war, they emerged as military and political leaders.

In every part of Afghanistan, powerhas changed hands multiple times in the last four decades of war, pitting different alliances of armies and militia forces against each other and leaving Afghanistan open to manipulation from outside as the various forces sought foreign backing. The cycles of violence and retribution triggered by the bloody violence of the Saur revolutionaries, in hindsight, can be seen to have set Afghanistan on a course of seemingly endless war. That conflict has now consumed generations.

1. Edwards, citing Taraki’s statement in the Kabul Times, August 16, 1978.

2. Anthony Hyman, Afghanistan under Soviet Domination, 1964–91(New York: St. Martin’s Press), p92.

3. Louis Dupree, “Red Flag over the Hindu Kush,” American Universities Field Staff Reports (1980).

4. Nabi Azimi, “Ordu va Siyasat Dar Seh Daheh Akheer-e Afghanistan” (“Army and Politics in the Last Three Decades in Afghanistan”) (Peshawar: Marka-e Nashrati Mayvand, 1998), p167. Cited in Afghanistan Justice Project, Casting Shadows: War Crimes and Crimes against Humanity: 1978-2001, p12.

5. Amnesty International, Afghanistan: Violations of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, pp15-16.

6. Amnesty International, p9.

7. Olivier Roy, Islam and Resistance in Afghanistan (Cambridge University Press, 1986), pp95,

8. Barnett Rubin interview with Sima Samar, 2004, cited in the UN Mapping Report, p12.

9. Hyman, p108, citing TheKabul TimesMay 3, 1979. After Amin overthrew and assassinated Taraki in September 1979, he renamed AGSA the Kargari Istikhbarati Muassisaas (KAM), the Workers Intelligence Agency.

10. Afghanistan Justice Project, p21.

11. Afghanistan Justice Project, pp17-19.

12. Afghanistan Justice Project, pp17-19

13. Afghanistan Justice Project, p19.

14. UN Mapping Report, p24, citing the UN report on the situation of human rights in Afghanistan, E/CN.4/1986/24.

By Special Arrangement with AAN. Original link.

Disclaimer: Views expressed on this blog are not necessarily endorsed or supported by the Center for Research and Security Studies, Islamabad.