As this dispatch was finalised, the Pakistan government had not made any last-minute extension to the ‘Proof of Registration’ identity cards for Afghan refugees residing in the country. Those cards were due to run out on 31 January 2018. Without an extension, a huge number of people could be forced to go back to Afghanistan in the middle of winter and to a volatile security situation. Pakistan has been a generous host to Afghan refugees for almost four decades, but in the last couple of years, it has displayed increasing inhospitably towards them. In 2016, it pushed out over a half a million Afghan refugees to Afghanistan, and as AAN’s Jelena Bjelica and Ali Mohammad Sabawoon report, there are now fears of a repeat of that forced exodus.

In June 2016, Pakistan pushed back over a half a million Afghan refugees, many with only a few days’ notice, as AAN reported at the time (see here). This expulsion was linked to the authorities’ decision not to extend the Proof of Registration (PoR) cards, the temporary identity cards that some Afghans residing in Pakistan have had access to since 2007. (Afghans with PoR cards are called ‘registered refugees’; those without are called ‘undocumented’ and are often treated like illegal migrants by the Pakistani authorities; for a full explanation, see this AAN dispatch).

2018 seems to have started with equally harsh intentions. “There will be no extension [of the Proof of Registration] after 31 January and they [refugees] will have to go to their country,” a senior official in the State and Frontier Region (Safron) ministry told the Pakistani newspaper Dawn in the mid-January.

Politics and PoR cards

Pakistan’s position on not extending the PoR cards, according to the Pakistani newspaper Tribune, was taken in view of both the increasing hostile attitude of Kabul and the pressure tactics of Washington towards it. Aizaz Ahmad Chaudhry, the ambassador of Pakistan in the United States, also commented on 19 January 2018 on Afghan refugees in Pakistan, saying they had turned into a security threat for their hosts. “Their youths are rented by terrorist groups,” he said. “We will deport both Haqqanis and Taleban to their own country including the Afghan refugees living in Pakistan.”

The turn in US policy towards Pakistan – President Trump said there should be increased efforts to persuade Pakistan to stop supporting the Taleban (see this AAN analysis) – and its deployment of more troops to Afghanistan, coupled with Kabul’s strengthening ties with India (see this AAN analysis here), all appear to have fuelled Pakistan’s reluctance to extend the PoR cards, hitting where it hurts, when it can hurt. Afghan refugees may well feel like pawns in a situation they have no control over.

A brief history of the extensions of PoR cards

In 2016 and since then, Afghan refugees have been on increasingly shaky ground when it comes to knowing how long they might be able to stay in Pakistan. Islamabad started providing Afghans with individualised computerised identity cards called Proof of Registration (PoR) in 2007, making them ‘documented refugees’. Although the cards were granted for only limited periods, they did enable holders to open bank accounts, purchase mobile phone SIM cards and get driving licenses. Most importantly, they provided a legal protection from arbitrary arrest, detention or deportation under Pakistan’s Foreigner’s Act. This improved the lives of many Afghans in Pakistan. In the beginning, the Pakistani government issued Afghan refugees with PoR cards for a period of two years or longer. The first PoR cards issued in 2007 were valid until December 2009. The second extension was until June 2013, the third until December 2015.

The PoR cards issuance policy became more ad-hoc and erratic in 2016 when the Pakistan government started extending the cards for only short periods of time, first, until June 2016 and, then, December 2016 (see this AAN analysis). In December 2016, under pressure from the international community, Pakistan extended PoR cards until March 2017. Just before the PORs were due to run out, on 24 February 2017, the Ministry of States and Frontier Region announced that the cards would be extended until 31 December 2017. The last one-month extension was granted by the Pakistani cabinet on its 3 January 2018 meeting. It allowed registered refugees to stay in Pakistan only for the rest of that month, until 31 January 2018. If it is not extended, the former card-holders refugees will have no legal protection from deportation.

Reactions to the 31 January deadline

In light of this Pakistan’s approach to Afghan refugees, the Afghan High Council on Migration held a meeting last week, at which President Ghani said that the refugees’ probable imminent return should be classed as a national emergency. The international organisations working with refugees and returnees have also been making efforts to help the Afghan and Pakistani governments reach a deal on this issue. Deputy head of the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) Sarah Craggs told AAN that IOM and other international organisations were still hopeful that Pakistan would extend the PoR cards, especially after months of significant high-level international pressure to do so. “There is some indication from Pakistan that they want to ensure dignified and voluntary returns,” Craggs said. “If extended,” said Craggs, “the PoR cards are likely to run through July 2018.” If that extension does not happen, she said it would put Afghanistan and its people “in a very vulnerable situation.” She called an extension “pretty critical,” saying if it does not come, “it will be extremely destabilising.” Craggs said that in 2016, “when there was a significant increase in returns, the humanitarian community launched a Flash Appeal and we may need to consider similar, depending on the situation.” She said that “returns over the past few years have already stretched resources, and there is a consideration of the absorption capacity…Most people [who have already come back] don’t have land and access to basic services.”

How many Afghan refugees have returned so far?

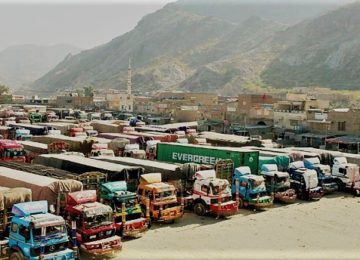

Already, since 2001, more than 3.6 million Afghan refugees have returned home from Pakistan. There was, initially, a huge push by UNHCR, international donors and the Afghan government to bring the refugees back – the homecoming was cast as proof that the new regime was popular. Also, in the first years after the Taleban regime was overthrown, conditions in Afghanistan seemed amenable to people re-starting their lives there. Over 1.6 million people returned from Pakistan in 2002. Between 2003 and 2015 between 50,000 and 400,000 returned each year. Then in summer of 2016, a huge number, on a scale not seen for over a decade, of over 600,000 Afghan refugees returned to Afghanistan (see this AAN analysis). Between July and early November 2016, UNOCHA reported, it was not uncommon to see as many as 4,000 people – sometimes more – pass through the border crossings at Torkham and Spin Boldak in a single day. Many were forced to return at short notice, after receiving 48-hour and/or a week’s notice to leave the country. They included those who had been living in Pakistan since the Soviet occupation (1979-89) when millions of Afghans sought refugee across their country’s borders. The younger ‘returnees’ comprise many who have never lived in Afghanistan. Some are even the children of those who have never lived in Afghanistan. Many of the returning Afghans have found themselves in a desperate situation in their homeland, with neither jobs nor proper housing.

The reasons for the mass returns in 2016, according to United Nations agencies and human rights organisations were fear of harassment and oppression by the Pakistani authorities (see this Human Rights Watch report (here and here), or in the case of undocumented refugees, fear of expulsion, as they are seen as illegal migrants and often subjected to arbitrary arrest, detention or deportation under Pakistan’s Foreigner’s Act. The first-ever Afghan government media campaign called Khpel Watan, Gul Watan (“One’s own homeland, a dear (literally flower) homeland”) aimed at encouraging Afghans to return ‘home’, also contributed to increased numbers of returns. (See this AAN analysis).

Last year, fewer refugees returned from Pakistan – 57,411 in total, according to UNHCR who supported them. In July 2017, however, the UNHCR, together with the Pakistan and Afghanistan governments, launched a programme to register undocumented Afghans living in Pakistan, estimated to number between 600,000 and one million. They should receive Afghan Citizen (AC) cards, which provide them with legal protection from arbitrary arrest, detention or deportation under Pakistan’s Foreigner’s Act. The AC cards also allow Afghans to stay in Pakistan for the time being, until they can be issued documents, such as passports, by the government of Afghanistan. The initiative was a significant step aimed at regularising the stay for many Afghans at a time when return to their home country may not be possible.

Since 1 January 2018, only 1,573 undocumented Afghans returned from Pakistan. There has not been any return of documented refugees because the UNHCR repatriation programme is closed during winter.

This all adds up, according to IOM estimates, to about 2.4 million Afghans still residing in Pakistan: 1.3 million are refugees, ie people registered with Pakistani authorities and in possession of PoR cards; 1.1 million undocumented of which 900,000 have been registered with AC cards, but not all them have been granted yet, and 200,000 people still in limbo with neither PoR nor AC cards.

Impact of a push back on Afghanistan Pakistan

Following Pakistan’s decision of 3 January 2018 to extend the PoR cards for one month only, IOM’s Craggs told AAN that the Afghan government came up with a contingency plan, which includes ‘proactive diplomacy’ and ‘advocacy for gradual voluntary return’. Proactive diplomacy included the Afghan Ministry of Refugees and Repatriation (MoRR) approaching the Pakistan government with a request for an extension. Rohullah Hashimi, the advisor for international affairs at MoRR told AAN that they asked Pakistan “not to mix humanitarian issues with politics.” He added that they were waiting to see “how much the Pakistani government was serious in its decision.” He insisted MoRR did have plans for returnees, including providing settlements for some within existing communities and opening camps for others in provinces bordering Pakistan. “We have already talked to UN agencies and international NGOs in Afghanistan and they promised to assist us,” Hashimi told AAN. However, the Afghan government does not have a good track record on supporting returnees; in 2016, despite openly inviting refugees to come back to Afghanistan, primary services like health and education in border provinces were not prepared for the influx of people (see this AAN analysis).

The return of a huge number of Afghan refugees would definitely put enormous pressure on Afghanistan. The Afghan government has been struggling to provide services to those that returned in 2016. Any returnees in 2018 would need not only food, employment, shelter and basic services, but a secure environment in which all of these services can be delivered (see this AAN analysis about 2017 security trends).

Any push back of Afghan refugees will also have some impact on Pakistan. Despite the fact that the majority of the refugees living in Pakistan are poor and Pakistan sees most of them as an economic burden, they, nevertheless, contribute to Pakistan’s economy with their skilled and unskilled labour. In 2016, when Pakistan decided to push Afghan refugees back to Afghanistan, a newspapers from Balochistan province in Pakistan wrote that, after the Afghans refugees withdrew their money from their bank accounts, in just a few days, the banks were emptied.

Instead of a conclusion: People’s concerns

Afghans residing in Pakistan are worried about a possible push back. The fact that the PoRs have not been extended beyond January is particularly problematic as the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees’ (UNHCR) voluntary repatriation programme, a key mechanism that provides for the returnees documented with the Pakistan government with some help to return, is closed during the winter months. The programme, that has been running since 2002, provides 200 USD cash per individual holding PoR cards. Children under the age of five are not entitled to cards, but are marked on the backside of one of their parent’s card and also receive the same amount.

Nur Muhammad, a shopkeeper living in Loralai district of Quetta is in a typical position for an Afghan refugee in Pakistan. He told AAN that if he is forced to return, he does not know what he will do with his business. “I have a business of nearly six million Pakistani Rupees (approximately 55,000 USD) and have already paid the annual rent of 360,000 Pakistani Rupees (approximately 3,500 USD) for 2018 to the owner of the shop,” he explained. If pushed back to Afghanistan, he said, “What should I do with this money and business?” He said the government of Pakistan had given them a one-month notice and when we spoke to him, on 29 January, there were just two days to go and no news as to whether it might extend their PORs. “If the Pakistani government wanted us to go to our country, it would have been better if they had warned us at least four months in advance.” He has additional worries: Faryab is insecure, he said, and he would not dare to transfer his family and shop there now.

Some local civil society organisations are also expressing their worries. The Afghan refugees committee from Peshawar, for example, asked the Pakistan government to allow for at least a one year extension. They highlighted that Afghan refugees in Pakistan are afraid of “insecurity, night raids by American forces, the presence of Daesh and Taleban.” These, they said, are the main factors hampering people’s decision to return. The Norwegian Refugees Council (NRC) also recently published a report calling on the different refugee hosting countries, including Pakistan, not to deport Afghan refugees at a time when security is deteriorating in Afghanistan.

Both refugees and agencies are worried about a possible mass push back of people across the border at a time when Afghanistan is not safe, services and employment opportunities for returnees are not evident and they would not have had time to prepare themselves. The question is whether these humanitarian concerns are equally important to those with the power to decide their fates.

By Special Arrangement with AAN. Original link.

Disclaimer: Views expressed on this blog are not necessarily endorsed or supported by the Center for Research and Security Studies, Islamabad.